This is the first part in a series of three commentaries about color, fashion and society

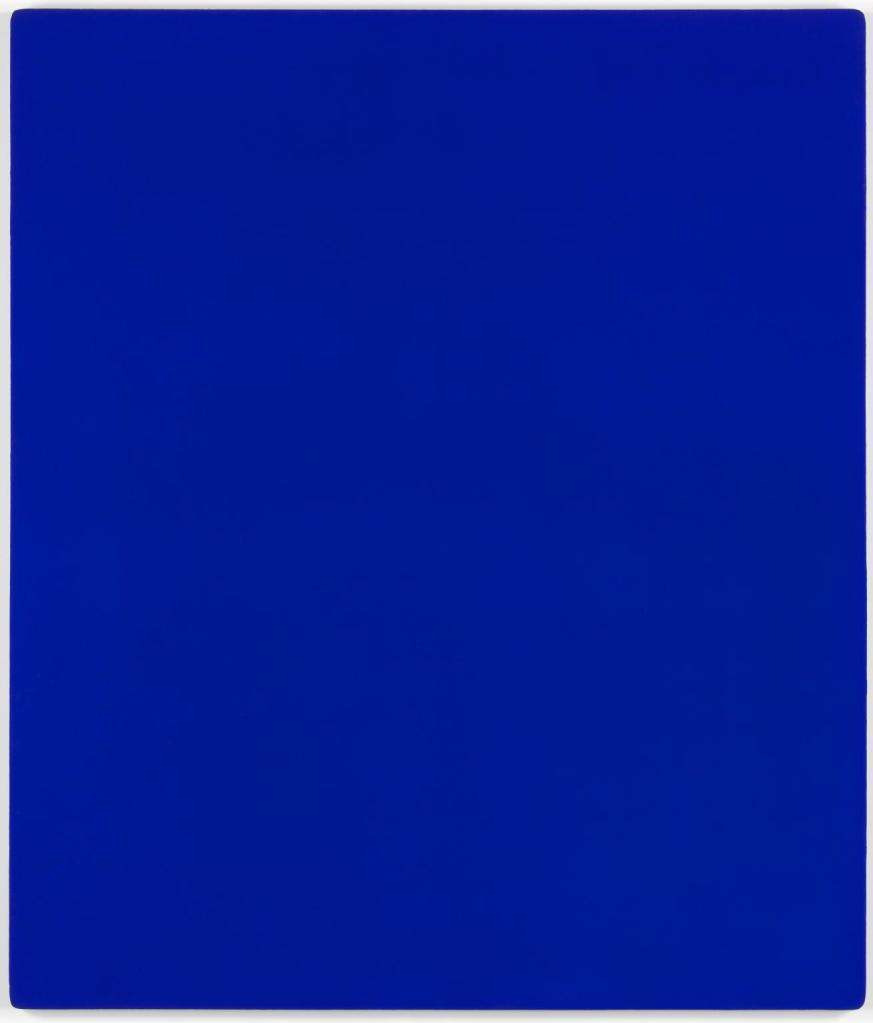

I’m reading Michel Pastoureau and having the slightly embarrassing sensation of discovering something that was always in front of me. I love fashion. I wear color. I can talk for hours about a silhouette or the cut of a trouser, about whether a shoulder is “right” for a decade, about the psychology of a skirt length. But Pastoureau’s writing makes me realize that, in my own daily practice, color has often been secondary, not absent, just treated like the finishing touch, the mood garnish. I choose a cobalt sweater because I feel alive, not because I’ve interrogated what cobalt has meant historically, socially, symbolically. Pastoureau’s point is precisely that this gap, between how much color does and how little we study it, is not personal; it’s cultural.

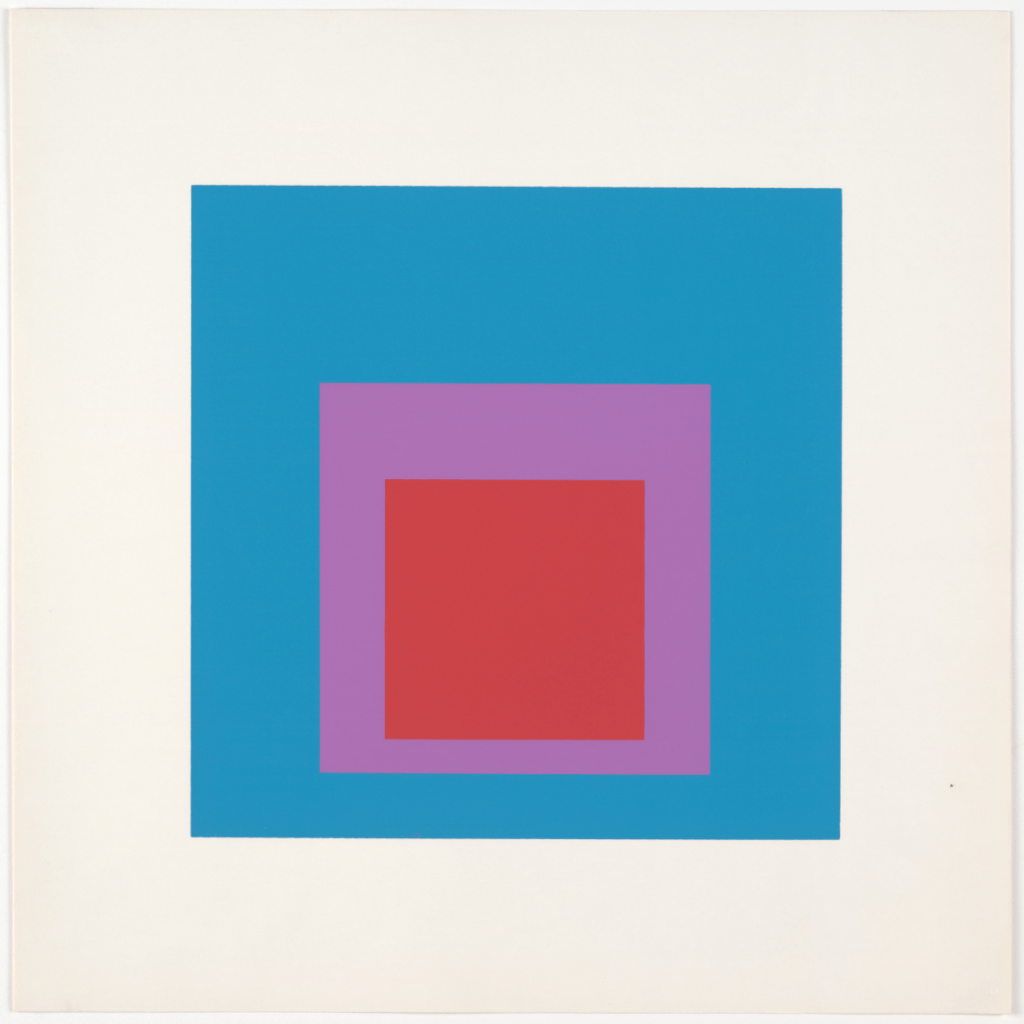

His foundational idea is that color is not merely a physical phenomenon. It is a social fact: a language shaped by norms, technologies, institutions, and power. What counts as “pure” white or “true” black is not only about pigment but about what a society agrees to recognize as white or black, and who is allowed to wear it, in what contexts, and with what moral charge. Even the basic boundaries of color categories have histories. If you’ve ever felt that “navy” and “black” are almost the same until someone with authority declares they are not, you’ve already felt Pastoureau’s argument in miniature.

Pastoureau also highlights how color has been treated as intellectually unserious compared to form and line, an inheritance from long Western hierarchies where drawing was associated with reason and color with sensation. You can still see this in how we talk today: we analyze structure, we enjoy color. In museums, viewers are trained to admire composition and brushwork; color is praised as atmosphere. In fashion, we do the same thing. The cut is architectural, the color is a pop. It’s not that color is absent; it’s that it’s constantly positioned as secondary, as if it arrives after meaning instead of generating meaning.

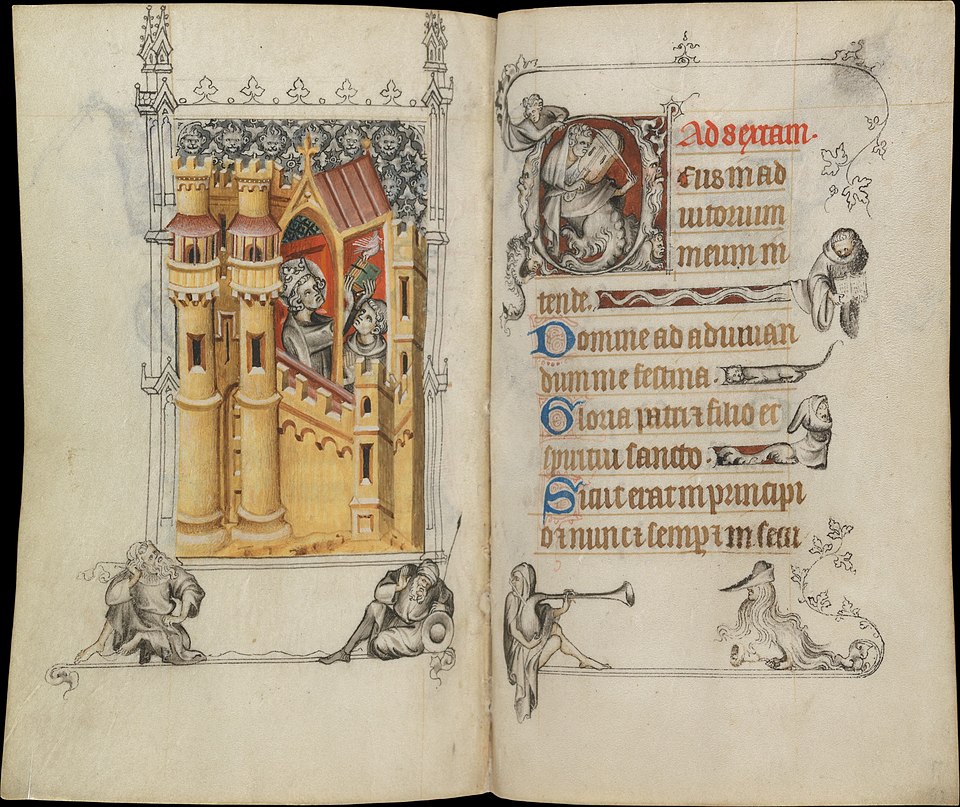

Historically, color has been one of the hardest-won forms of luxury because it was tied to material scarcity and technical difficulty. Certain dyes were rare, unstable, or expensive; some required long, laborious processes; others faded quickly, which made them socially risky. That’s why color so often becomes a shorthand for power. Imperial purples, saturated reds, deep blacks, these hues still echo authority because they once required control over resources, labor, and knowledge. Luxury has always trafficked in difficult things, and Pastoureau makes clear that color belongs to that economy.

Fashion becomes a particularly revealing archive because it carries color into public space. Painting stays on a wall; clothing moves through streets, offices, trains, restaurants. Color in fashion is judged instantly and collectively. A head-to-toe beige look isn’t merely neutral; it signals restraint, understatement, a certain contemporary ethic of cleanliness. A neon jacket can be read as youth, attention, risk, frivolity, or freedom depending on who is looking. The same garment in different colors becomes almost a different moral proposition.

This is where I recognize myself. When I dress, I think silhouette first how I want my body to read: sharp, soft, protected, elongated. Then I think practicality. Then color arrives as mood: today I want energy, today I want calm, today I want to disappear. I rarely ask what this color historically does to my social legibility, or what institutions trained me to read it this way. Pastoureau doesn’t ask us to intellectualize every outfit, but he reveals that color already governs us quietly, whether we acknowledge it or not.

Fashion media reinforces this hierarchy. We talk endlessly about the return of the waist, the new proportion, the death of skinny jeans, as if trend were primarily geometry. Color is reduced to seasonal atmospheres and digestible labels: earth tones, pops of red, washed pastels. Yet color is often what reaches the public first. Not the subtleties of cut, but the impression that a season was dark, bright, muted, or brown.

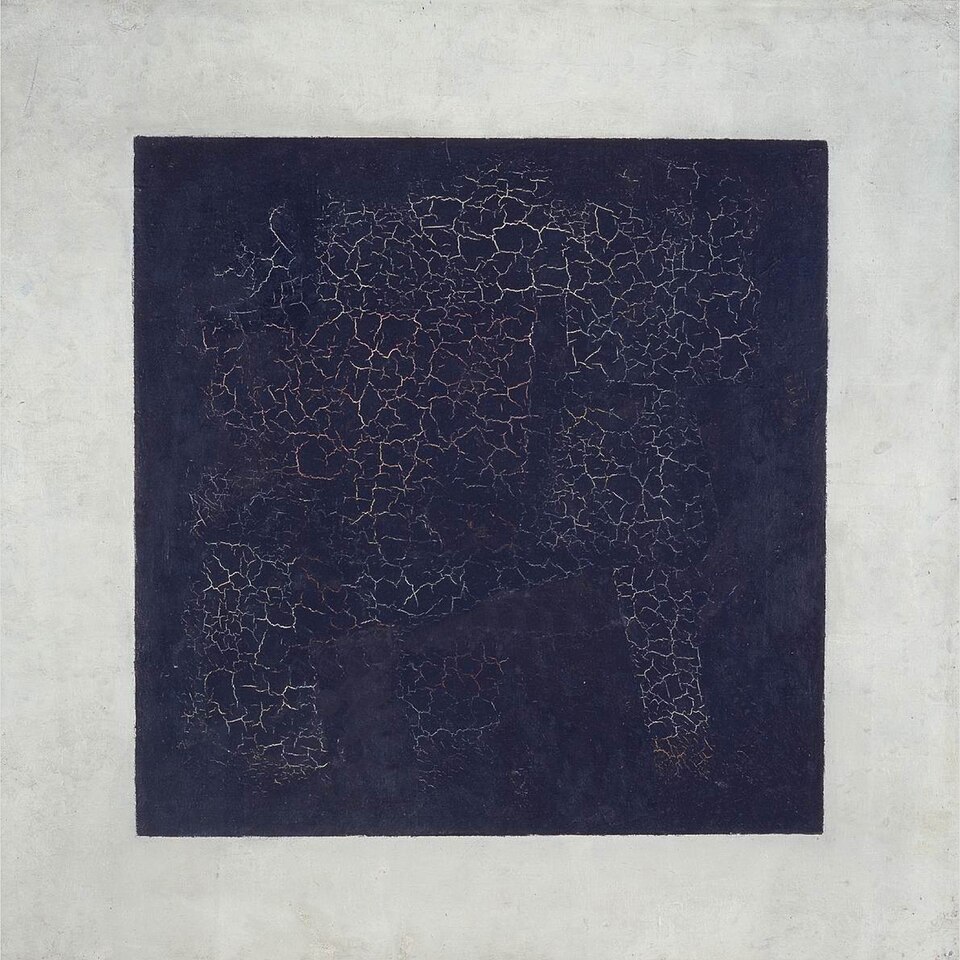

Luxury intensifies this dynamic because it sells permanence while surviving on novelty. Color is the most time-stamped element of an object. A black coat can pretend to be eternal; a very specific pistachio cannot. So luxury often treats color like a controlled substance, allowed in limited doses, formalized through house codes, contained in accessories or seasonal capsules. Black, navy, camel, cream, and white function as a safe-deposit palette: they age well, they signal investment, they promise longevity.

Pastoureau also makes visible how color becomes moralized. Certain palettes are described as elegant, clean, refined, loud, cheap, or childish. These aren’t neutral judgments; they are social ones disguised as taste. The contemporary prestige of neutrality is not just aesthetic minimalism. It is restraint as virtue, efficiency as beauty, self-control as status. Color preference becomes political without announcing itself.

The more I read Pastoureau, the more color stops being my feeling and becomes my historical participation. I still dress based on mood, but I now see that mood itself is trained. We learn what calm looks like, what competence looks like, what authority looks like. Color is a vocabulary whose grammar we inherit. And perhaps the most intellectual conclusion is this: color is not merely an expression of who we are, it is one of the ways society teaches us which selves are acceptable to perform in public.

Leave a comment