In 2003, Takashi Murakami and Louis Vuitton launched one of the most radical and commercially successful collaborations in fashion history. At the time, the Maison was dabbing with collaborations with contemporary artists under the creative leadership of Marc Jacobs. This year, it’s back. Reissued. Reframed. Repositioned. Or maybe just repackaged. What is certain is that artistic collaborations have become an independent staple for the Maison, removed from what Nicolas Ghesquière and Pharrell Williams offer for the runway.

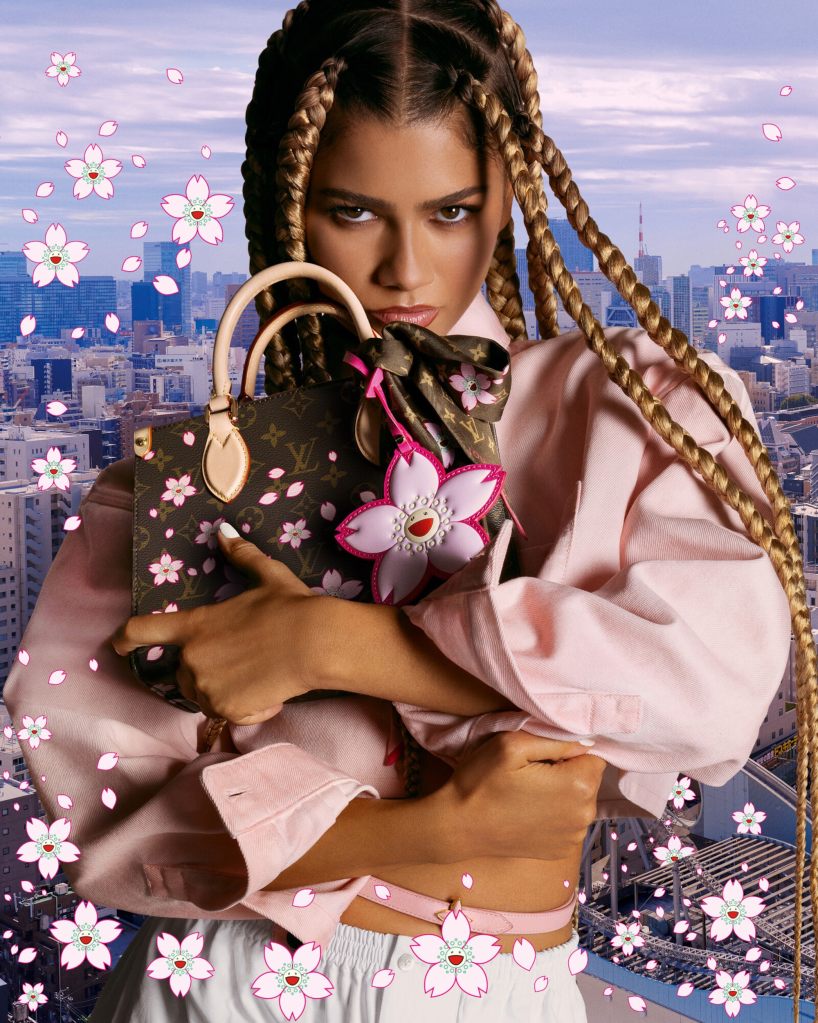

Let’s start with scale. This isn’t a casual archive drop. It’s a full-scale, three-part relaunch: a re-edition of key pieces from the original collaboration (Multicolore, Cherry Blossom, Panda), a digitally animated campaign flooded across social, and a curated “retrospective” moment in stores, complete with immersive installations and archive storytelling. Beyond the nostalgia many fashion addicts mention as a reason why they are buying into the collection this move is part of a more complex strategy.

Louis Vuitton is making a statement about legacy, authorship, and its place in culture. The question is: what exactly is that place? The re-release comes just a year after the second wave of the Yayoi Kusama collaboration, a campaign that leaned heavily on art-world language but offered little in terms of actual reflection. No evolution of form. No shift in message. Just more polka dots, new products, same script.

Murakami’s reappearance raises similar questions. Is this a retrospective, the kind a museum would stage to trace an artist’s progression? Or is it just a rerun dressed up in curatorial drag? Because if this is about showing how Murakami’s vision has evolved, the collection does not show it. These are the same pieces. Same symbols. Same logic as 20 years ago.

Superflat, Murakami’s philosophy, is about collapsing hierarchies between art and commerce, East and West, high and low. It worked in 2003 because it was disruptive. It asked real questions about taste and value, especially for an industry like luxury, where performativity has become cornerstone. Today, the tension feels dulled and already overexploited. Superflat is no longer a provocation, it’s has become a brand asset.

To be clear, this doesn’t make the collection less interesting. The bags still hold up visually, culturally, and in resale value. But what is really missing is friction. If this is art-world logic, then where is the critical distance? Where is the evolution? Where is the curatorial voice? It does not need to be provocative, but challenging enough to leave us with questions.

The risk of becoming political is legitimate for a brand like Louis Vuitton that does not want to take part in its time woes. The tension between speaking to the contemporary customer while remaining timeless and relevant across generations is at the core of the industry. Yet, art is, by default, political and speaking about and to its day and age. But art also goes beyond our limited humanity, it lasts and resonates across time. Each time asking new questions about our conditions. The message is not about the artwork, but about the viewer. The opportunity to shape meaning is real, and Louis Vuitton seems to be shying from it.

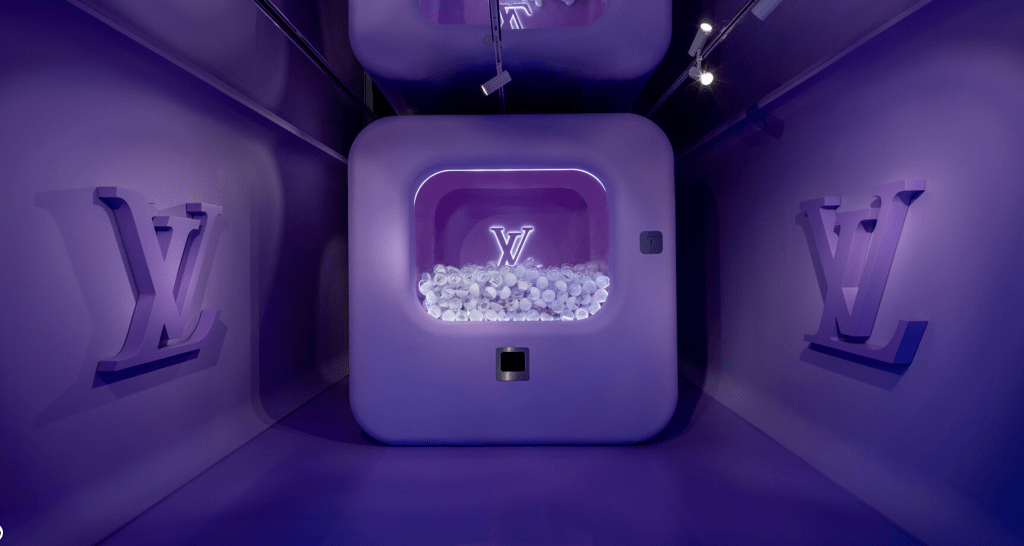

What Louis Vuitton seems to be doing instead is doubling down, not on the art, but on itself. The house is positioning its archive as a museum and its stores as gallery spaces. It stages collaborations like asseptized curated exhibitions, complete with artist bios and custom packaging. The bags become limited-edition prints. The campaigns mimic art catalogues. The logic is not fashion, but institutional. Legitimation through repetition.

So what is the message? That Louis Vuitton supports artists? We already knew that. That fashion can be cultural? Yes, but it already is. The real statement might be more internal: Louis Vuitton is culture. Full stop. Not adjacent to it. Not inspired by it. But synonymous with it.

Which is powerful. But also closed. Because when a brand starts acting like a museum, it runs the risk of freezing itself, turning what was once living dialogue into canon. And canon, as we know, rarely asks new questions. So yes, the Murakami pieces are back. But what are we really looking at? A reinterpretation? Or just a very glossy rerun?

Leave a comment