It has been a busy year for the luxury world. Arguably, it has been an even busier year for me. While I am still processing this life parenthesis, it is time to get this blog back on track. Indeed, I took the decision to carve more time to go back to what I like most: art and fashion.

To start off this come back, I want to discuss the arrival of Jonathan Anderson at Dior. In early June, JWA was confirmed at the helm of one of my favorite luxury houses. This applies to both men and women. Kim Jones (formerly doing Dior Men) and Maria Grazia Chiuri (Women) will be missed, and I cannot wait for their future endeavors. Similarly, JWA will be dearly missed at Loewe which skyrocketed both culturally and commercially under his leadership. Let’s see what the future holds for the Madrid Maison.

JWA is not new to the intersection of art and fashion. He collaborated with numerous contemporary artists while at Loewe: Lara Favaretto, Lynda Benglis or Anthea Hamilton are among my favorites. He gave them a stage. But this time, his approach is slightly different. At Loewe, Anderson had almost a cultural blank state in terms of references beyond the house codes. This was despite Loewe being the oldest fashion house of the LVMH group. But Dior comes with a rich history and cultural capital. A series of star designers before him have built on this.

And in fact, the fashion, the communication, and the staging of the Men’s show were about inspirations and references, not getting contemporary artists under the spotlight. « When I thought about how to expand the horizons of the Maison, I thought about Christian Dior, whom, after the Second World War, looked back to the past to create the New Look » said Anderson. Yet, the subversiveness of JWA’s style transpires in the designs, showing his willingness to bridge tradition and modernity.

The fashion is where this tension is the most prominent. The Dior Delft dress and its folds inspired a wide androgynous pair of shorts. The collars on straight shirts were purposely crooked while perfectly ironed. Ties were mixed with Canadian tuxedos. Delicate flowers adorned heavy Irish-inspired knits. Bows and jellyfish-leather shoes flirted and traditional tailcoats cohabited with chunky sneakers. Soft pinks and grey hues, among Mr. Dior’s signature colors, sprinkled the looks through the show.

References to traditional inspirations went beyond the house of Dior with tote bags referencing Dracula by Bram Stocker (1897), Les Liaisons dangereuses by Pierre Choderlos de Laclos (1782), Bonjour tristesse by Françoise Sagan (1954) and a sentence Dior by Dior. Maybe a wink at the storytelling abilities of a designer who was as much of an artist as a publicist.

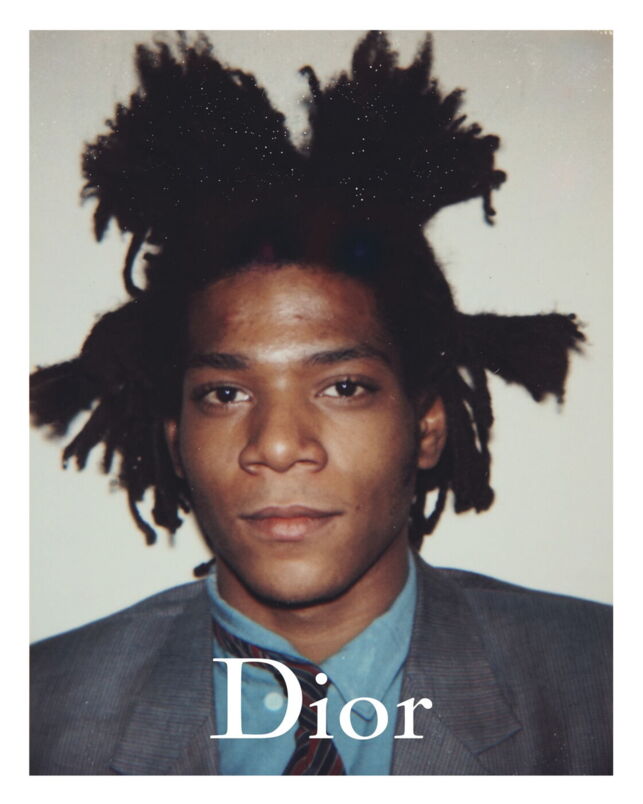

The totes were also among the first communication assets shared by Dior on social media. They encapsulate this dance between conceited tradition and unstructured modernity. Established as a Maison icon under Maria Grazia Chiuri, the recent success of the piece is anchored in time with references from before its creation. Similarly, the pictures of Jean-Michel Basquiat and Lee Radziwill by Andy Warhol for the first campaign, embody this challenge of bridging worlds. « Wearing Dior is being stylish. That is why I chose portraits of Jean-Michel Basquiat and Lee Radziwill. They do not have anything in common, came from completely different backgrounds. But they had style.»

Finally, the location and setup of the show was expertly crafted. It played on the weight of traditional references at the brink of being challenged and remodeled. The venue was staged in front of the Invalides, a symbol of French military. It displayed a large replica of Dior’s Salon Avenue Montaigne where all of Dior’s shows took place. The cultural simulacrum was reinforced as guests entered the venue. The walls were adorned in grey velvet and golden wooden floor. This setup replicated a room from the Gemäldegalerie of Berlin known for best enhancing the colors of the paintings.

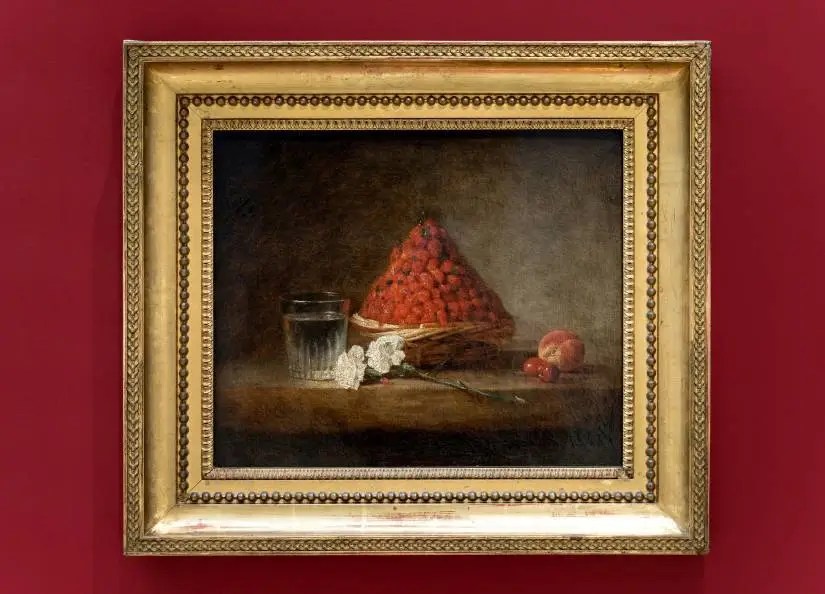

The space also welcomed two paintings effectively transforming it into a museum. The works were still lives from Jean Siméon Chardin (1699-1779). One of them, Le Panier de fraises, was borrowed from the Louvre (of which LVMH is a sponsor). The other, Un vase de fleurs, is on loan from the National Galleries of Scotland. Chardin is among Anderson’s favorite painters as he sees in him « an approximation announcing impressionnism ». Maybe he identifies in this approximation about to transform the Maison Dior.

To conclude, Anderson continues to use art and its references to serve his purpose. Yet, he skillfully tilts the scale to tell a different story. One thing that I have always admired, is his ability to speak to the complexity the zeitgeist. Anderson not only understands it, but he also knows how to make his audience understand it too. He does this in the most striking yet intricate way. As always with him, I cannot wait for more.

Leave a comment