The status of Andy Warhol as a precursor of pop art does not need further illustration. He was a visionary whose impact is still spectacularly tangible. First, in the art world with for example Takashi Murakami to cite only him. Second, in the commercial world with consumerism still being a defining characteristic of Western cultures. “All department stores will become museum, and all museums will become department stores” said the artist in the 1960s.

And indeed, the increasing importance of art to boost experiential retail is luxury in a perfect example of this. While the trend is not new, it has accelerated since the restrictions following Covid-19 have rescinded. According to the BoF-McKinsey The State of Fashion 2024 report, executives plan on increasing their physical footprint in 2024 by almost 50% around the world (p.17), despite financial headwinds and mounting global uncertainty. The store is back at the center of commercial strategies.

As art has become a fully-fledged branding strategy for several Maisons, especially in the LVMH family, it seems only natural that stores resemble museums. While the opposite is not exactly true (yet), the striking resemblances in presentation cultivated in stores necessarily spills on the experience the luxury customer has of the museum.

Already more than a hundred years ago, in his book The Art of Window Display (1900), Lyman Frank Baum advised of taking inspiration from practices used by museums: “What constitutes an attractive exhibit is what arouses the observer cupidity and a longing to possess the goods you offer for sale”. This sentence underlines two main points of interest.

First, the difference between institutional and up and coming art: the quantifiable degree of attractiveness. And secondly, the combination of art pieces/products and the way these are presented to entice interest. All these aspects can be combined to achieve different strategies within the luxury and fashion industry. Coherence will depend on matching the brand identity and whether the products are hard or soft luxury items.

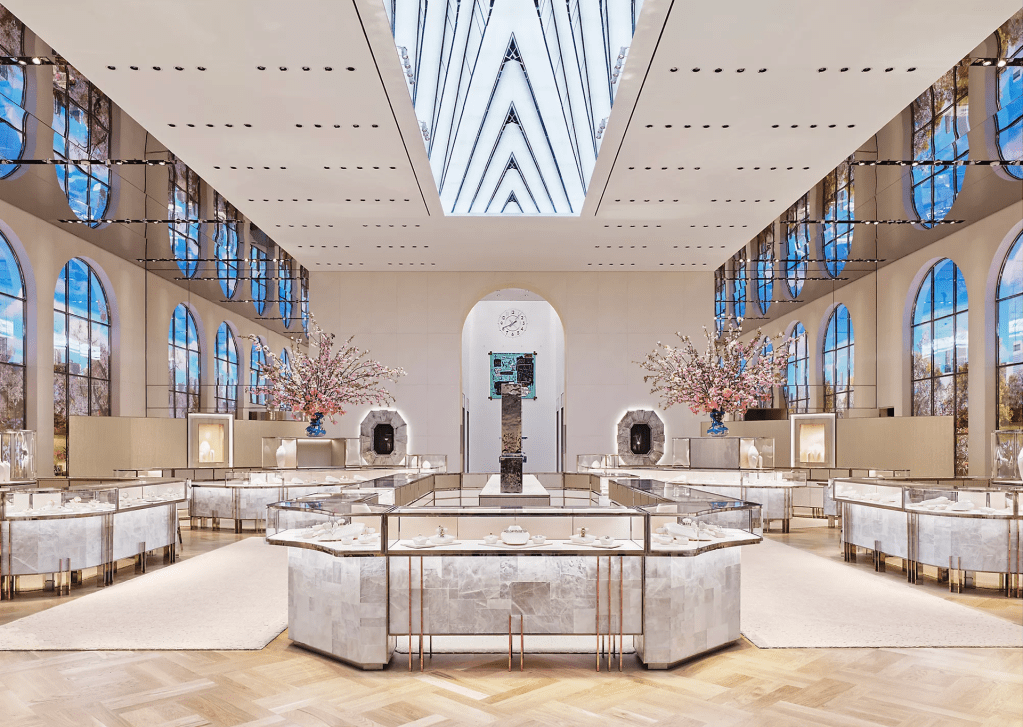

To illustrate my point, let’s take the example of the Tiffany & Co flagship store in New York, redesigned by starchitect Peter Marino. Bought by LVMH in 2020, the brand, products, and stores have been thoroughly revamped by the luxury behemoth with Alexandre Arnault being named VP Products & Marketing. Reopened in 2023, the Landmark on Fifth Avenue is a 10-flights building featuring shopping areas, private salons, and a café. The Tiffany Blue Box Café makes Breakfast at Tiffany’s an actual option.

Critically, the Landmark is not only a place to shop, but also a place to meet the brand. Immersion, experience, and exceptionality are quintessential in the space featuring large glass displays and actual artworks with commercial undertones. Tiffany is a good example because before the acquisition by LVMH, it was mainly known for diamonds, and “Return to Tiffany” locks. It was successful mainly in the US and China and a lackluster rival to European leaders as for example Cartier.

Jewelry is traditionally a hard luxury product where craftsmanship, exceptional quality, and design as well as the rarity of the raw material usually suffice to justify the price point but Tiffany also as a large range of more affordable pieces closer to soft luxury. In any case, the brand needed to reboot its brand image to grow sales and recover its former glory.

Brand story, identity, heritage, emotions, and lifestyle, supported by cultural references and icons are all front and center in the Tiffany strategy and are visible at the Landmark where the different prongs of the strategy meet in mastermind merchandising and store design. At a high level, museum presentation practices meet museal objects elevating the preciousness of the products but also making them relevant to the time since the art presented in mainly commercial. The strategic decision strikes the right balance in speaking to both highbrow HNW consumers and more trend-forward hype-oriented clients.

Precious objects are presented in glass shop windows with product explanations and designer highlights: from Elsa Peretti to Jean Schlumberger, like it would in a museum. The process to select and shape Tiffany diamonds is explained in an interactive case. The space is laid out so that circulation is both organic and guided. Semi-circular presenting areas follow each other in what feels like succession of groves one could find in a French garden. Windows are screens opening on a magical imaginary landscape, an Immersive Moving Fresco by Oyoram Visual Composer.

At the back of the first floor in front of the elevators, the now famous Tiffany egg-blue Jean-Michel Basquiat, with which the Carters posed for the first campaign of the brand under the LVMH helm. At each floor, art one could find in a gallery or even a museum is displayed: Andy Warhol, Anish Kapoor, Daniel Arsham, Damian Hirst are sprinkled across the floors. All these artists are blue-chip institutional names, from modern or contemporary art, particularly aligned with the hard luxury ethos of the brand. At the same time, they are modern pop artists that refresh the relevance of the brand and its ability to speak to the zeitgeist.

Tiffany does both art pieces and museum presentation techniques, particularly fit for hard luxury that is valuable in and of itself without the storytelling. The addition of artworks does not necessarily elevate the pieces but enhance the story of the brand, inscribing it among the big creative names of our time.

In this example, one can see the store is not only the vessel of sales but also a space of identity and story-building in the same way museums create a story about an exhibition or an artist. A piece by itself is only fully understandable once contextualized. And contextualization can be used and abused to frame a story and make pieces tell exactly what one wants them to tell. Merchandising, store design and museology, therefore, share not only some of the same display and presentation strategies but also some of the same goals in getting a point across through the unique experience of the display of objects.

With customers putting increasing importance on experience and living the brand, this relation between art institutions and luxury commercial spaces in only likely to grow. While the shop is being transformed into a museum, the museum is not yet a shopping place, even for the ultra-rich.

But collaborations between auction houses, selling some of the artists present in museums, and luxury houses is far from being far-fetched with Hermès bags routinely appearing at Christie’s or Sotheby’s for example. Louis Vuitton’s stand at Art Basel is again just one of the many examples of blurring the lines. Was the stand displaying art or bags, or both? And what does it say about Art Basel, the galleries presented there, and the Louis Vuitton brand?

Leave a comment