Now in its seventh iteration, the Dior Lady Art project gives carte blanche to a handful of carefully selected artists to reinterpret the Lady Dior bag. It is arguably the most iconic handbag from the storied French fashion house, and one of the most iconic handbags in the world. Initially introduced in 1994 under the creative direction of Gianfranco Ferré, the bag was coined “Chouchou” but became the Lady after Bernadette Chirac gifted it to Lady Diana, who sported it so much that the House decided to pay her homage and rename the bag after her.

The classic item made from 144 pieces of which 43 are metal parts, assembled in Florence, is already an apt canvas for declinations season after season and designer after designer. Maria Grazia Chiuri, currently at the helm of the Maison has reinterpreted the bag with various motifs and materials from constellations to flower patterns. Traditionally made from cannage-quilted lambskin, the motif is a tribute to the Napoleon III and Louis XV chairs guests were seated on during the fashion shows Avenue Montaigne.

In line with Maria Grazia Chiuri’s willingness to collaborate with artists on and off the runway (from Judy Chicago to Mariella Bettineschi to cite only those), the initiative introduced in 2016 (the same year she started at Dior) is an opportunity to showcase up and coming artists. It is also a way to expand the cultural significance of the Lady Dior – and by extension, of the Maison Dior. Interestingly, the bag’s shape is the same as a canvas, helping in the versatility of possible reinterpretations. Plus, the “box” shape draws some similarities with the idea of the museum as a “white box”, shaping ideas and our shared understanding of art history and culture.

Taking the examples of Alex Gardner, Shara Hughes and Sara Cwynar helps in understanding the dual role of the object as a medium of and as a piece of exhibition. First, Alex Gadner, reproduced one of his famous pieces, “Malleability”, on the canvas with iridescent leather and velvet details. It is worth noting that the square bag allows him to replicate the tension between what is on the canvas and what is not.

Most of his pieces feature faceless characters in relationship with the liminal space of the scene questioning gender identity and race. Here, the detail of the hand allows the viewer to participate in imagining the rest of the scene and identify with the seemingly trivial scene. Like a bag that can be reinterpreted and styled, the scenes favored by Gardner are sublimated versions of our casual individual yet collective experiences.

For Shara Hugues, her reinterpretation of the bag focuses on creating windows framing her works, ‘Prelude to the Future’ and ‘Midnight Hike’. She uses the bag as a literal frame elevating and complementing her work playing on the relationship between inside and outside of a bag or a box. “As a painter, you’re asking somebody to enter into your world,” she said during a podcast for Dior. She thrives on “go(ing) to the edge of something without explaining everything all of the way” leaving some space for interpretation for the viewer.

She makes clear references to nature, one of the favorite subjects of Christian Dior famous for his “femmes fleurs” and uses a color palette reminiscent of the French Nabis. Yet she did not alter her work to fit in Dior’s framework, choosing to play with the possibility offered by the bag in enhancing the story of her work. By choosing to focus on the surrounding artificialities, in many ways, she goes against the now popular tradition of museums striping artworks from contextual surroundings.

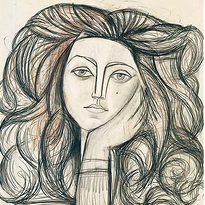

Indeed, we tend to forget that museums are societal meta-structures resulting from a particular interpretation of history. The museum, being more than a repository of artifacts, reflects the decisions made by curators and art institutions that led to a dominant discourse. While there are obvious conversations between artists like Picasso and Cézanne, for example, the choice of which movements mattered more than others is purely the result of institutional forces. Oftentimes in the West they were – and are – representative of the white, patriarchal establishment. In short, museums are the product of an ideology.

They were decisively ornate and traditionally pompous at the time of their institutionalization in the 18th and 19th century in Europe, since they were inhabiting ancient palaces like the Louvre, or imperial buildings aiming at representing the superiority of knowledge like the British Museum. Yet, most museums now have white walls and a bare environment. This trend started in the 1930s with Alfred H. Barr, the first director and curator of MoMA and has resulted in the “white box” theory.

Defined by O’Doherty in his seminal series of Essays in 1976, the exhibition practice aims at presenting the art pieces in their most neutral environment, in order to let pieces speak for themselves and let viewers experience them without interference. Paradoxically, this curatorial decision also frames the “right” way to look at art. To put it simply, the way things are presented is as important as what is presented.

This dynamic of structural framing is even more potent in the work of Sara Cwynar. By deciding to use the cannage canvas as frames for images taken from museum archives and art history books as well as trivial popular images of lips and cars, she equates the bag to a mini museum, or a Cabinet of Curiosities, the Renaissance ancestor of the Museum. “I wanted to make a kind of encyclopedic object, a mini history, that someone carries around on their arm,” says the artist. But, as for any museum, she curates a story. Inescapably, the choice of images, their disposition in relation to one another, and the color chosen as background conveys an ultimate message of institutionalized luxurious glamor, fun and taste.

Her approach is similar to artists choosing the museum as their subject of study, like Hubert Robert who painted the corridors and rooms of the Louvre in the 19th century – a parallel that can be extended to the walls of the main gallery in the Louvre, painted in red. The inside of the bag depicts clouds and a sky, which allows one to enter another world, as one enters a museum as a space of elevated knowledge.

Additionally, the enterprise shares some similarities with the concept of (D)iorama which can be defined as “a scenic representation in which sculptured figures and lifelike details are displayed usually in miniature so as to blend indistinguishably with a realistic painted background”, a concept which the Maison Dior has declined in many, many, many (I mean it) instances.

At the upper echelon, for Dior, this whole enterprise is a curatorial exercise whereby they claim institutional legitimacy. This is done through their selection of 11 artists, and their choice of “canvas”/“boxes”, namely, their bags which become art pieces while being art repositories. Far from being aseptic pieces, the Lady Dior bags are by themselves legitimate cultural symbols shaping taste. With the Dior Lady Art project, the brand establishes that luxury institutions’ choices matter as much as museal institutions’ choices, and that, maybe, the “white box” as the best way to present artworks is an outdated approach.

In fact, digitalization, globalization and the growing cultural significance of fashion houses means that museums are progressively sharing the spot in shaping the narrative of artistic creation and art history, thereby redefining exhibitions’ audiences, media, and ideologies.

Leave a comment