Andy Warhol undeniably shaped culture as much as he was inspired by it. His impact on art history and society cannot be overstated and the countless reinterpretations of his work by creatives globally are a direct reflection of the impact his work still has on our common psyche. Olivier Leone, co-founder and Creative Director of Nodaleto shared with me his vision for their latest campaign inspired by the pop artist. Warhol’s legacy is as complex as it is accessible, which helps in explaining why his work is still relevant today.

For Michael Dayton Hermann, Director of Licensing at the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, part of what makes Warhol’s work so prescient is the mirror it continues to hold up on American life – and truly Western culture. Understanding how Warhol’s methods were anchored in the social stakes of his time helps in casting light on the efficiency of re-using them in order to make a contemporary claim for Nodaleto. Leone underlined that part of what attracted him to Warhol’s work is the fact that he used to be in advertising before being recognized as an artist, and that he has been alternatively praised and criticized by the establishment. Through Warhol’s eyes, art becomes more accessible while material culture becomes more exclusive.

Nodaleto’s latest campaign blends several signature tropes explored by the famous artist – and artist of fame – to make a point concerning the state of our materialistic society. At the same time, it embodies Olivier Leone’s and Julia Toledano‘s experience in building their brand. Titled “Nodaleto’s 15 minutes of fame”, after the quote attributed to the artist “In the future, everyone will be famous for 15 minutes”, the campaign is mainly distributed though social media with pictures and short videos. Indeed, the latter have allowed for anyone to be famous overnight and have fueled our collective obsession with fame. “Today more than ever, we live through each other’s gaze.” says Leone, and @tags are our new validation system, our new establishment.

Leone shared that the exponential success of their brand right after launching pushed them to reflect on its status within their industry and within the cultural zeitgest, and in fact on their own potential 15 minutes of fame. He underlined that since Covid, it even seems to be 15 seconds of fame, or the length of an Instagram story or TikTok video, as our attention spans are reduced by the ever growing amount of information thrown at us and available at our fingertips. Hence, paradoxically, we all know more than ever and less than ever.

Andy Warhol is mostly known for his serigraphed paintings made in his New York’s Factory and through which he explored his obsession with icons and with reproducibility, blended in both subject and medium and relevant in analyzing Nodaleto’s campaign. The brand uses Warhol’s language to elevate their shoes to the rank of cultural icons, as the team “treated their shoes like human beings” said Leone. In Warhol’s work, stars from Marilyn Monroe to Jackie Kennedy to Elvis Presley and even Warhol himself were reproduced in series underlying their importance as references known by masses. He was also obsessed with commercial culture, the mainstream and mass production as testified in the Campbell Soup Cans.

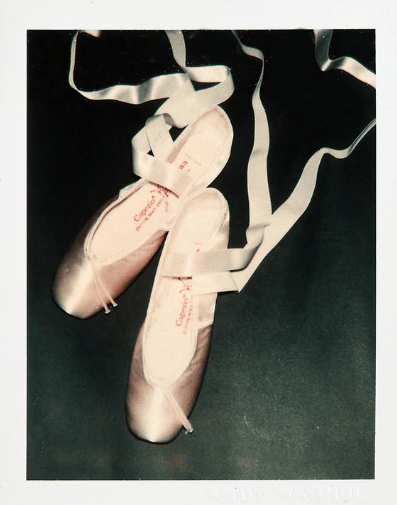

When it comes to the polaroids that inspired Leone, who stressed their color scheme, Warhol expressed they were mostly a diary, and he often took his surroundings (famous people included) as subjects. At the same time, the triviality of some of his shots is a testimony of the material culture of the second part of the 20th century. Objects – like Nodaleto shoes – were a privileged subject of Warhol’s work, thereby rendering them uncommon since they were made into art. Yet, the infinite reproduction of artworks turns them back into commodities. “Someday, all department stores will become museums, and all museums will become department stores” said Warhol.

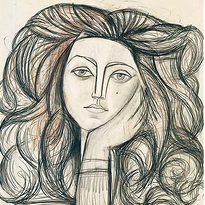

Nodaleto’s campaign is replete with both references to his shots of common objects, like bananas or pairs of shoes, and to his close-ups of body parts, like in the Sex Parts and Torsos and Ladies & Gentlemen series. Polaroids were a way to document his obsession with the body and sexuality and Leone stressed that Warhol’s back and forth with Antonio Lopez in exploring the subject is directly referenced in the campaign. Photography was the first medium to allow for a mass-scale, instant reproducibility of images at the end of the 19th century, and was progressively established as a artistic medium in its own right during the 20th century. John Baldessari said Warhol “helped to bring photo-imagery under the umbrella of art – to deghettoize it”.

Photography was critical in the development of pop art and its powerful hold on society. It allowed for the reproduction of works that used to be unique, leading to question the intrinsic characteristics of a piece of art. Walter Benjamin, in his essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” (1935), established that the intent of the artist, more than the medium, credits the authenticity of the artwork. “Even the most perfect reproduction of a work of art is lacking in one element: its presence in time and space, its unique existence at the place where it happens to be” justified Benjamin. But this subtlety is exactly what pop art challenges.

To understand the resonance of Warhol’s work, one needs to understand the cultural shifts that happened during the 20th and 21st centuries. There is no debate that art is the expression of a certain culture, and there is no need to demonstrate that religious art used to be the main driver of art history, at least in the West. In short, art was representative of a certain culture’s values, beliefs, and rituals and was thereby attributed a unique meaning. Yet, as the cultural discourse became detached from religion through the phenomenon of secularization, art’s meaning, and eventually, subjects shifted.

Photography, and then film (with which Warhol also experimented), because of their ease of use and distribution, have become our main media of visual communication. This leads to a constant reinterpretation and activation of artworks, coupled with a dislocation from its traditionally unique meaning. Therefore, art comes to be created for drastically new reasons: the medium has shifted the purpose. “The work of art reproduced becomes the work of art designed for reproducibility” says Benjamin. Mechanical reproducibility contributed to the attention shifting from religious icons to practical, tangible, and material… icons.

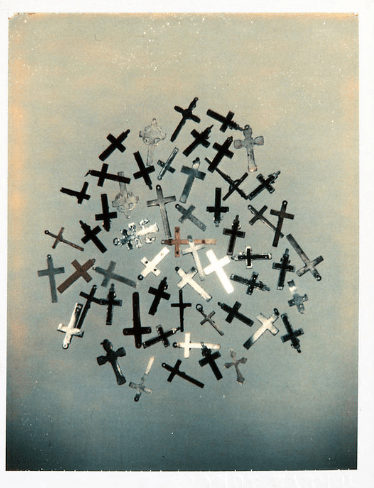

In this respect, even if only investigated by art historians in the past ten years, Warhol was in fact deeply religious, although it remained secret during his lifetime. If it sounds surprising when one considers the eccentricity of the transgressive, openly gay artist, Warhol actually displayed strong references to his religious upbringing in his art as demonstrated by the Brooklyn Museum. His mother – with whom he remained close his whole life – was an extremely religious Protestant. Pinpointing the contradictions of Warhol’s Catholicism, yet, underlines the complexity of the messages Warhol was relaying in seemingly simple terms.

From the reproduction of the Last Supper to Gold Marilyn reminiscent of the Virgin Mary on golden backgrounds characteristic of Byzantine and Orthodox art, Warhol understood that the language of religious faith had to be translated in secular terms. In a society that worships fame and mass consumption, Jesus and the Virgin Mary have less cultural grip, but the ways of framing worshiping still call to deeply entrenched references, even if unconsciously. And in fact, “Fashion and the Catholic Imagination” at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2019, proved this is still the case.

Nodaleto, by directly referencing his work and creative process, is therefore establishing its shoes as a new cultural icon. But it goes one step further as the brand updates the medium to our age: digital reproduction. When asked if he thought the glossy commercial images were becoming less relevant in the fashion industry, Leone replied “Yes, it is what Instagram has told us”. But he stresses that it reflects a shift in Instagram’s business strategy towards more real content. “People still want to dream” he said, and there is some demand for the brands’ voluntarily commercial approach, maybe not on Instagram… They intentionally resist the pressure to fit in: their page is extremely curated, with irregular postings and no behind the scenes, arguably setting them apart and explaining their high organic engagement.

Leone stresses that in our society of “new is always better”, we tend to overlook the great things created in the past, and that by bringing back an old style of shoes they want to share a slower creative pace fueling quality over quantity. “We forgot how to get bored, but getting bored is good, it leads to creativity”, he says. Through this creative reflection – in fact a common theme of the brands’ visual (and material) language – Nodaleto offers a contribution to the current curatorial stances taken by many luxury brands. “With references to the masters of photographic composition and female led performance art, the new visual approach strives to play the role of an art gallery” claims the brand.

Nodaleto is not trying to gain cultural capital by referencing fine arts, but aims at contributing to it, confirming commercial and material culture are among the most relevant vectors of cultural enrichment nowadays. At the same time, the mise en abyme of commercial art quoting fine art itself stemming from commercial culture establishes the brand as a cultural actor aware of its limitations. When I asked about what he thinks Warhol’s Instagram account would look like if he had one, Olivier Leone insisted that it is hard to speak for someone else but thinks it would have been organic, understanding that instantaneity has taken over complex reflections. “In reality, maybe he would not even have been good” he said, having to step away from his magazine-like approach.

Arguably, the age of digital reproducibility is responsible for redefining creativity, and by demonstration, culture-making once again, which is why Nodaleto’s expansion of Warhol’s discourse is so clever. Paul Valery quoted by Walter Benjamin said “We must expect great innovations to transform the entire technique of the arts, thereby affecting artistic invention itself and perhaps even bringing about an amazing change in our very notion of art.” What is certain is that Nodaleto thrives in blending past and present to anchor their legacy beyond 15 minutes of fame: their next campaign will feature one of the main faces of a tremendously popular show of the past ten years involving dragons, and I, personally cannot WAIT to see the result…

Leave a comment