Since joining Dior Homme in 2018, Kim Jones has become well versed in the space of collaborations, from LVMH-owned label Rimowa, to contemporary artists like Daniel Arsham and KAWS. He usually invites collaborators to redefine and explore the visual identity of the Maison in their own languages, creating hit collections that impress and create hype beyond the season they were designed for.

Yet, his decision to work with The Antonio Archives is different for at least two reasons: instead of working with a contemporary artist, he reinterpreted the designs of two dead artists, in a sort of reverse creative collaboration. The second element is his effort to expand the identity of the Fendi Maison, still in relation to, but beyond Lagerfeld, which was, it is impossible to deny, a monumental figure of which the shadow is hard to get out of.

Since taking the helm of Fendi in 2019, at the death of Karl Lagerfeld, Jones has been taking his marks in the storied women-operated label, working alongside Silvia Venturini Fendi and her daughter Delfina Delettrez Fendi. His first silhouettes were deemed harsh and stoic, recalling the Roman columns of the Italian capital in which the house was founded. For his SS22 collection, yet, he proposed a lighter, more feminine disco take on the codes of the Maison, astutely digging around the history of the label, and focusing on partying and going out after the lockdowns digital shows.

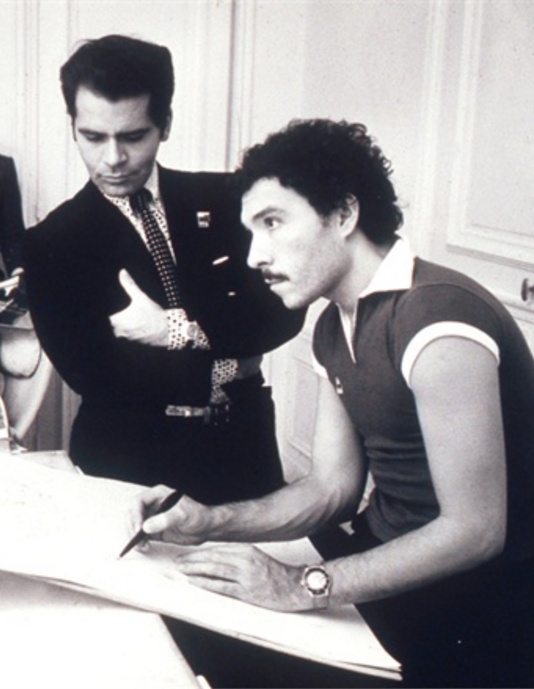

Indeed, he dived into the archives of the Maison and decided to collaborate with The Antonio Archives, responsible for the estate of Antonio Lopez and Juan Ramos, famed fashion illustrators of the 60s and 70s. Their link to the Maison goes through Karl Lagerfeld with whom the two creatives were friends during the time they spent in Paris in the early 70s, before a fallout.

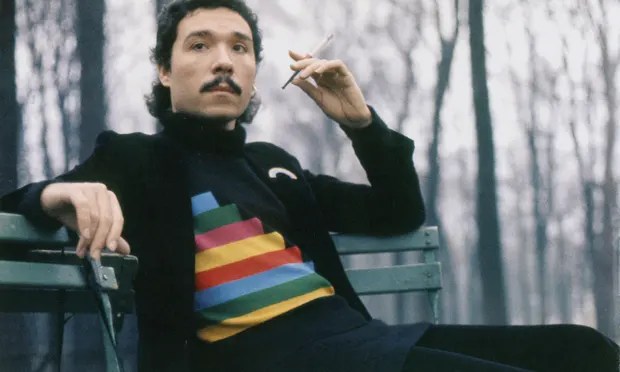

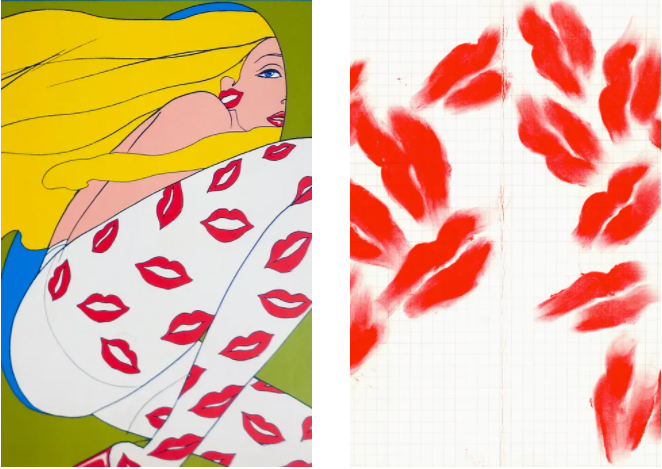

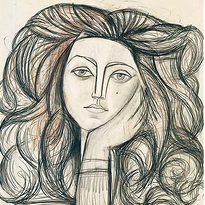

Antonio and Juan met in New York during their studies at FIT and were romantic partners for several years. Starting to work for Women’s Wear Daily during his curriculum, Lopez did not graduate to pursue the WWD opportunity full time, in close collaboration with Ramos. They were famous for their light and bold designs and use of colors as well as their exploration and representation of the queer identity that was flourishing in NYC. They were also among the first creatives to work with models of colors and unconventional beauties, as early as the 60s.

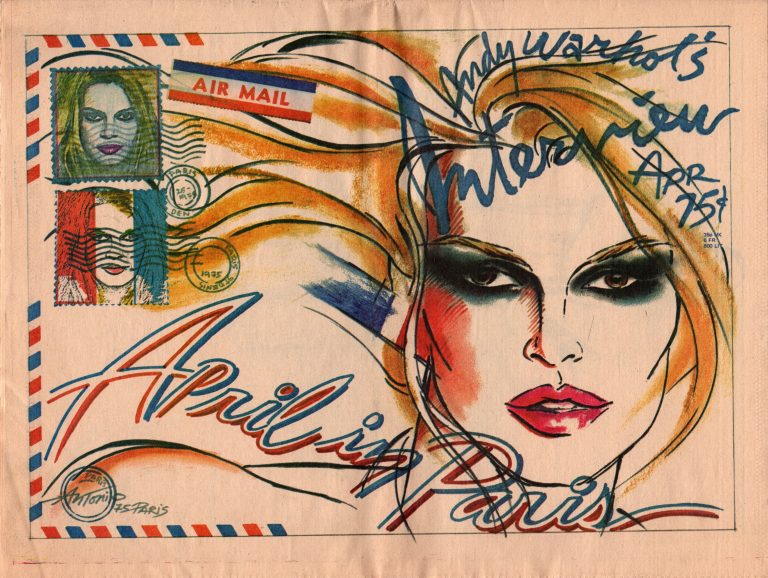

In 1969, feeling that the norms and conservative rules of the society they lived in constrained their creativity and lifestyle – Lopez was momentarily engaged to Jerry Hall whom he helped establish – they decided to move to Paris, where they lived in one of Lagerfeld’s apartment, spending the Summers with him in St Tropez, and going to the buzzling club le Sept in the capital (documented by Alicia Drake in Beautiful People). They returned to New York in the mid-70s, no longer friends with the fashion designer at the time at the helm of Fendi since 1965.

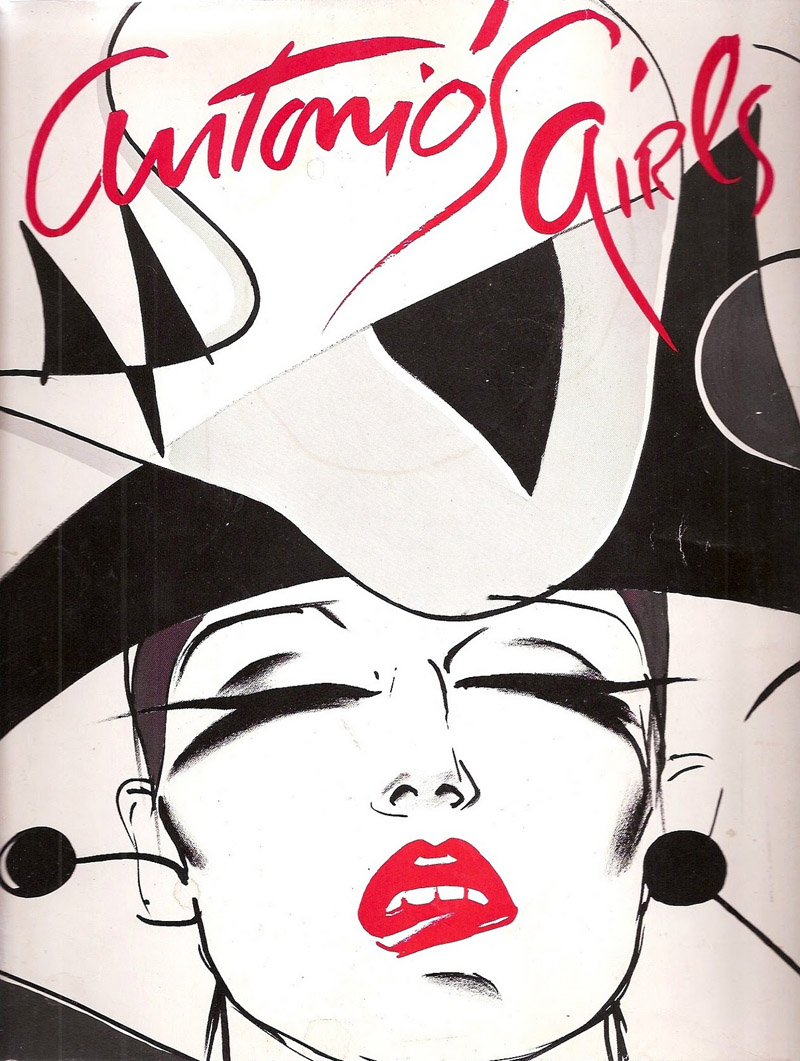

They opened a Studio near Central Park South and close to Andy Warhol’s Factory with whom they collaborated on two issues of his Interview magazine. Lopez was known for discovering talents that were coined “Antonio’s Girls”, some of them ending up working with Warhol (Donna Jordan and Jane Forth). Warhol was so fascinated by the duo that he actually made a film, L’Amour, in 1973, about the years the two creatives spent in France alongside Lagerfeld.

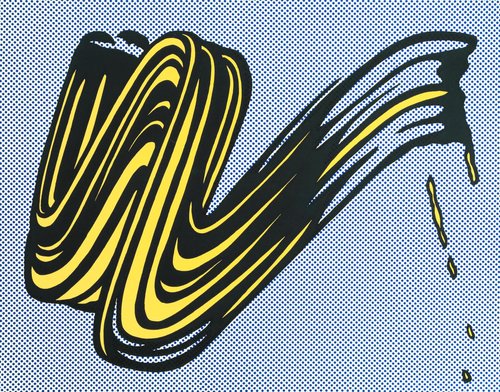

Warhol, Lopez and Ramos were in fact exploring the same subjects around ambiguous sexuality, although by different mediums, as Warhol branched out from his initial fashion illustration experience to become the pop artist we all know today. He was not the only pop artist with an illustration background and one can think about Roy Lichtenstein and Ed Ruscha who engaged into the same creative trajectory during the same period.

Lopez died prematurely from complications from AIDS in 1987, aged 44, while Ramos outlived him only until 1995, dying from AIDS too. The fashion and creative community, as well as their close collaborators, agree that if it was not for their early departures, they would have evolved to become key figures in the fashion industry and central tastemakers of the 20th century, as they were extremely aware of the power of image and self-presentation even before the rise of the selfie.

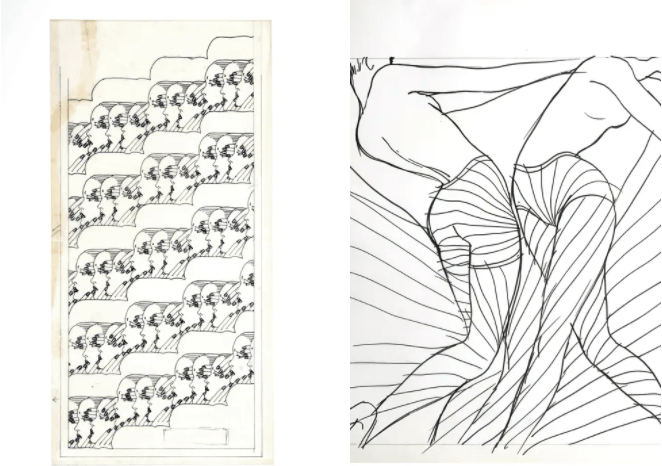

Furthermore “they borrowed styles from disparate eras, incorporating everything from Renaissance chiaroscuro, Bauhaus geometry, Art Deco patterns, and mass media motifs into their works.” according to their estate. Their practice testifies of an acute awareness and understanding of previous artistic movements, as expressed through their obsession for geometry and repetitive patterns visible in the architecture of the first part of the 20th century, inscribing their creation in the zeitgeist of the time beyond the fashion bubble.

Lopez’ and Ramos’ work flourished both through photography and illustration, but the bold vivid lines and the confident sexy poses of their models displayed in Vogue, Harper’s Bazaar and The New York Times helped fashion illustration remain relevant at a time where photography was becoming fashion’s main medium of image-making. In fact, the former editor of French Vogue Joan Juliet Buck says the illustrator convinced her the “ideal life is lived through a line drawing”.

Jones, therefore, decided to go beyond the deterioration of the relationship between Lagerfeld and the duo, to honor the exceptional creativity of their designs and give them the recognition the industry has not been fully acknowledging. From a Fendi logo found in the archives written and styled by Antonio, the redesign of some of Antonio’s drawings to fit on signature bags, dresses, and clothes, Jones offers a new take on these works, infused with his interpretation.

The caretakers of The Antonio Archives, painter Paul Carnicas and his niece Devon Caranicas, based in Jersey City in New York City where the two collaborators were both from (both Puerto Rican from the Bronx), underline the exceptionality of this collection since Jones reinterpreted the works he borrowed from his visit to the archives. As The Cut puts it, he effectively bended Antonio’s powerful influence towards his own creative vision.

Indeed, ArtNet notes that “though he wasn’t the first to pay homage to the artist’s work—a 2017 Kenzo collection by Carol Lim and Humberto Leon famously featured it—Jones brought it to life uniquely through the infusion of his own ideas and motifs inspired by those of Lopez, in lieu of faithfully reproducing them on his pieces.”

According to the Estate’s blog “the works that Jones and his team utilized didn’t rely on the celebrity images that Antonio and Juan are typically known for, but instead focused on textile-forward subject matter that showcased the wide range of contemporary and historical references that A & J so liberally applied to their editorial and commercial work.”

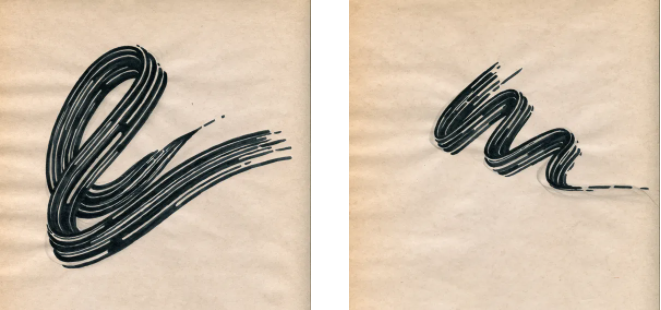

For Devon Caranicas, “What’s so exciting about Fendi is that they’ve not so literally translated the artwork.” A paint brush drawing ends up adorning dresses and caftans, while women’s profile initially intended for a packaging project elevates fur coats, Fendi’s signature fabric, with gray, red and green lines. The brushstroke is a clear reference to Roy Lichtenstein and embodies how pop art is embedded in every aspect of culture, and that fashion is a fertile support for its iterations, explorations, and reinterpretations. Dresses, jackets, boots, all got a tweak to present entire bold and colorful silhouettes infused with Antonio’s designs and aura.

The Baguette, Peekaboo and the Croissant become quintessentially pop items coming to life with leather appliques of women’s body parts riding striped-rainbows, colors of the LGBTQ+ community to which Lopez and Ramos belonged to, and expanding the reach of the cultural conversation opened by the Maison. As mentioned by Alicia Drake in The Beautiful Fall, Lopez was one of the first to show that Black, brown, homosexual, trans, and working class could be glamorous.

Their inclusive creative process resonates with current fashion trends and the evolution of the industry towards more diversity. Beyond redefining the visual identity of the constrained Fendi codes Jones is learning to work around, this collection is a political and cultural stance firmly asserting what Fendi stands for. In fact, Jones wanted to introduce Lopez to a new generation that cares about those same social and cultural causes.

Here, Jones masterfully presents how the work of artists can be interpreted in a new way through collaborations where the designers take a more important role in the creative process than only stamping the cut of the clothes, and, potentially hints towards a different way to work with past and contemporary artists within the fashion industry.

Leave a comment