It seems to be a common place that fashion is a means of communication. It is a way to express one’s self and show to the outside world what one is about on the inside, or rather, as one wishes to be perceived by others. This semantic implies that fashion has meaning both for the person wearing it and the people interacting with someone’s look. In a way, fashion is a language like any other. But, contrary to a language formed of letters, words and sentences allowing for a more direct expression, fashion is a language of signs made from visual elements. Paradoxically, this allows meaning to be both more straightforward and more multilayered.

The particular language around fashion has been studied by the semiologist Roland Barthes in “The System of Fashion”. But he decided to only study the words used to describe fashion in magazines. That is the way the fashion industry translates the visual language onto the page through words to assign a meaning and a context to the fashion items and frame their understanding.

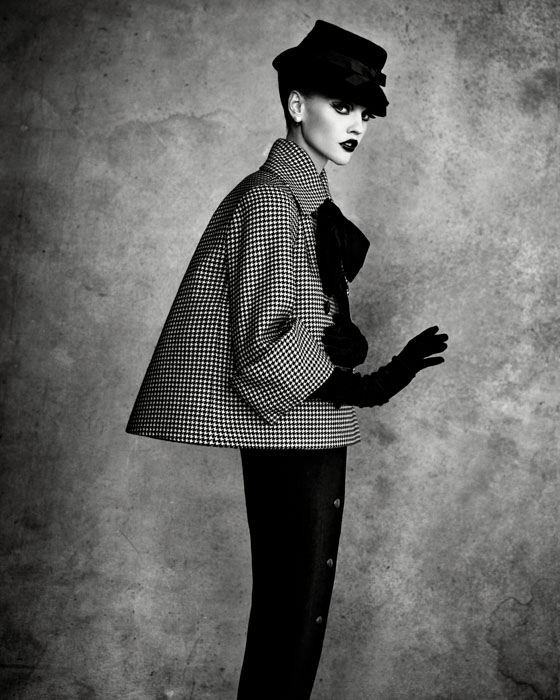

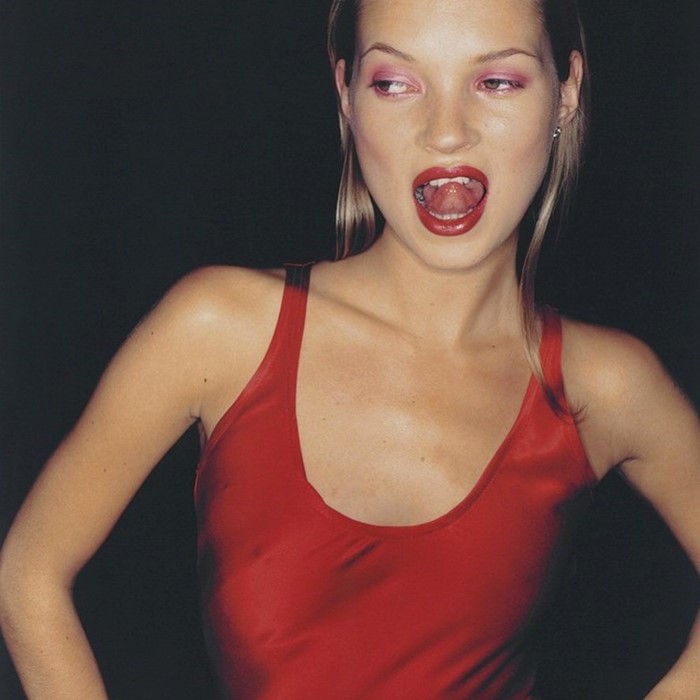

Here instead, I want to focus on the visual meaning attributed to fashion images, both through traditional magazines but also through social media. Barthes’ book was released in 1967, way before social media and way before the heyday of fashion photography during the 1990s (documented by @ninetiesmoments. This period marked the heyday of fashion photography as we know today, as an art form with photographers becoming icons, like the late Patrick Demarchelier.

Since then, print magazines have been losing their audience and fashion images have evolved to be an art form, creating a language akin to the one used by artists in visual arts, that is, a language revolving around symbolism. In his book, Barthes underlines that written language is one of the most complete and complex forms of language, while fashion at its core is similar to a more constrained form of expression using symbols akin to the one used for traffic laws. We all know what a red octagon means, with or without the stop on it.

In a way, the prominence of social media and images as the main medium to spread fashion has simplified the way to ascribe meaning to fashion since people engage more directly with the image without their meaning being framed by the fashion journalist. This has allowed for an expansion of the meaning attributed to fashion and a liberation of the rules ascribed to each and every piece of clothing, translated into the blurring of genres and situations where items are appropriate to wear.

Streetwear has now become a regular element of high fashion and the former strict rules of dressing at venues and events like the Opera has been significantly losing relevance. Yet, as the fashion image has become the main means of communication for the industry insiders and trendsetters, their quality and complexity has also evolved implying their message is framed with more subtlety than it used to be.

By making these images more straightforward, the photographers are astutely concealing all the tricks involved in the making of an image, very often distorting reality. If words are sometimes more powerful in distorting reality, our critical minds are by nature putting a filter when engaging with them, while it engages with realistic images in the reverse order, taking what the eye sees for granted before unpacking the details.

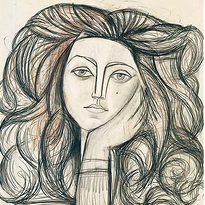

This evolution towards a simplified iconographic system conveying an increasingly broader set of meanings can be understood through the length of the evolution of the artistic movements during the second half of the 20th century marked by the rise of abstraction (Serra’s minimalism for example). Painting and art are quintessential forms of iconographical and symbolic expression, formerly conveying a semantic dimension at an even broader scale than letter and words, literally framing meaning.

During the Middle Ages, most Catholic European people across Europe did not learn to read and write and their main engagement with the religious scriptures was through art, paintings and glassworks in churches, where a significant amount of symbols were attributed to the figures represented allowing the worshipers to distinguish them. Now, a lot of these symbols have lost their meaning for most viewers, even those well acquainted with the Bible.

The semantic power of an image is arguably the most fleeting in terms of meaning because it is representative of a time and place, that is why its importance evolves throughout time and why scholars are needed to assign meaning to artworks, that is true for expressionist art and abstract art. But while expressionist art tends to lose meaning through time rather than being assigned a new meaning, abstract art focuses on the engagement of the viewer with the artwork and invites each and every viewer to ascribe a different set of meanings stemming from one’s personal experience and engagement with the artwork.

In the age of individualism, the societal understanding of a language is less important than the personal one. This observation is applicable to fashion as the social norms and rules that used to dictate this world have been loosening and originality has become the main driver of the industry.

At a dinner party last Saturday, we touched upon the subject of the meaning of popular culture in art that was intrinsically meant to become less significant as culture itself evolves and images that used to be ascribed a set of meanings become irrelevant. While I believe this holds some truth, I think one of the powers of pop art is its ability to constantly assign a new set of meanings to what we take for granted, or if it fails to do so, it is a testimony of the way a society used to engage with images at a certain moment in time.

Looking at Andy Warhol, arguably the most famous pop artist, I believe his work emcompasses all the ways an artist can convey meaning though popular images from creating icons (Campbell’s cans) by choosing to include trivial objects in his work, to using icons to elevate the relevance of his art (Marilyn Monroe), to assigning a new meaning to traditional artistic images (The Last Supper), to, most critically, conveying the way a society engages with the power of images.

Social media have become the main way to spread images and more than the iconographical language being used, the critical shift is around the quantity and pace of images. It is a testimony of the way our society engages with images, in a capitalist, consummerist manner. In a way, it is no surprise that it has become a fertile ground for the luxury fashion industry. It allows the spread of the power of images and the meaning ascribed to them at a faster and more global scale.

In a world where we all speak different languages but that is more interconnected than before, images are critical to spread a message. But, at the same time, by being a simpler form of expression, it allows for a multiplicity of meanings and interpretations. Trends have some forms of global impact but a local interpretation, inviting each and every wearer to a personal engagement with the fashion items, like abstract art encourages a personal engagement with artworks.

Leave a comment