There is no doubt Jonathan W. Anderson is among the most talented designers of his generation. Be it for his own label or as the creative director of Loewe, he proves time and time again that his creativity seems without limit. Yet, for the past two seasons, he seems to have taken it a step further at Loewe, tapping into surrealism and art history and asserting that fashion is indeed a form of artistic expression in its own right. I am still utterly obsessed with the collection of shoes featuring eccentric heels representing a cracked egg, lipstick, nail polish or roses from SS22. L’Officiel dubbed AW22 “a masterclass in wearable art.”

Last season, his creations were inspired by Pontormo and were responding to a post-pandemic effervescence. This time, he worked with English artist Anthea Hamilton and took her sculptural approach to materials into his clothing, pushing us to question what we take for granted in a deconstruction of shapes and fabrics focusing on movement. Ultimately JWA seems to be pushing us to question the established rules of fashion, art, and even society engaging into movements beyond surrealism like futurism, performance art, minimalism and pop art to cite a few.

The set of the show featured Giant Pumpkins, monumental half-deflated leather sculptures of squashes by Anthea Hamilton, famous for her big, surreal installations that invite viewers to wander around and reflect on their own physicality. Additionally, Hamilton’s 2010 banner, Aquarius, was an inspiration for the show; it portrays an idealized male form, akin to Leonardo da Vinci’s “Vitruvian Man”. She uses several materials and techniques and has been working with textiles notably for her in situ work for “The Squash”, commissioned by the Tate Modern in 2018 and realized in partnership with Loewe. This work featured people dressed in squash outfits walking around the galleries covered with over 7000 white tiles making it look like a public bathroom.

Hamilton speaks about her practice saying “I am interested in everyday things because we all know what they are”, she aims at making the ordinary extraordinary challenging our sense of familiarity, a philosophy visible in JWA’s creations as he challenges what we expect clothing to look like, feel like, even to be used for. His creations are as much objects of contemplation as actual clothes to wear, if not more so. Hamilton’s art is informed by pop art in the manner of Andy Warhol when it comes to the subject, and by minimalism and performance art when it comes to the presentation, as she invests large spaces and aims at making them come to life. In fact, the Loewe show presents all these aspects of her creative sensibility. “I make the work to be interacted with. I think a lot about the space around a piece as much as what happens inside of it” she says.

In 2016, she presented a large bottom for the Turner Prize recognizing contemporary artists in England, which was indeed a “Project for Door”, underlying the engagement with the body as a subject, recipient, and actor of art, again, all critical aspects in fashion. In 2017, with “The Squash”, she became the first black woman to be awarded a commission to create a work for Tate Britain’s Duveen Galleries, and according to Alex Farquharson, Tate Britain’s director, Hamilton has made a “unique contribution to British and international art with her visually playful and thoughtful works”.

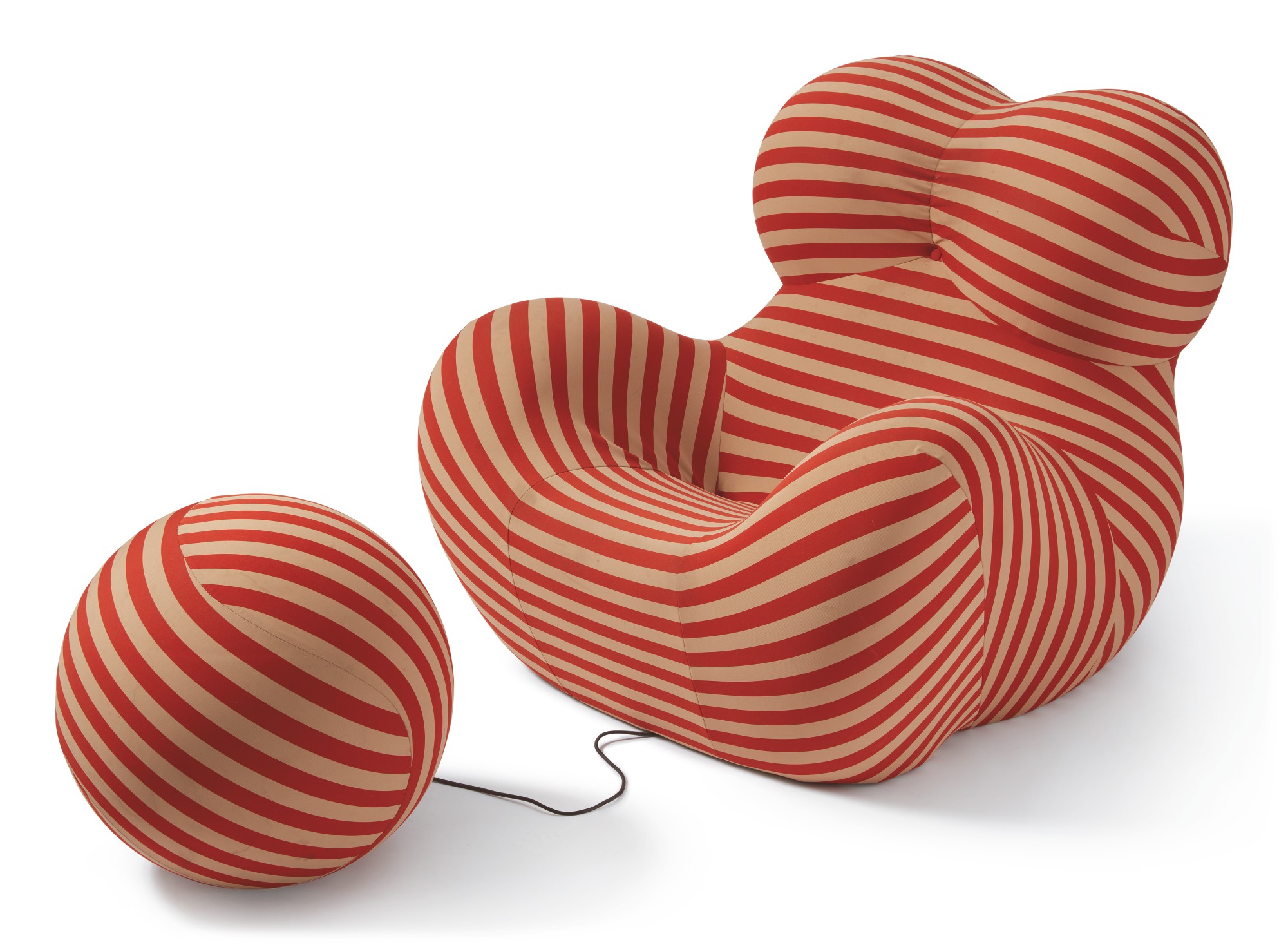

The artist defines herself as indecisive, but it is this versatility that allows her to stretch the relevance of her creativity across media, practices, and inspirations. The “Project for Door” was inspired by designer Gaetano Pesce, “The Squash” performance by an old photography by Erick Hawkins and “Superstudio Quaderna” works by Jean-Pierre Raynaud, at the intersection of the past and the present, her creations create a sense of nostalgia and the perfect playing field for envisioning the future by creating an out of time dialogue, a process dear to the artist. She is not interested in the idea of originality as much as in ownership of an idea and the conversation it sparks, she often engages with other artists’ works by taking direct inspiration from it, offering her own perspective as she loves to collaborate with other artists and creatives.

The artist said she is interested in “the idea of performativity within an exhibition context” turning the fashion show into a museum-like space, creating dynamics and engagement with, actually, the same type of creation-sensitive audience (that she is trying to expand). She thinks about her work as systems to be comprehended all at once, engaging the totality of the elements in an artwork.

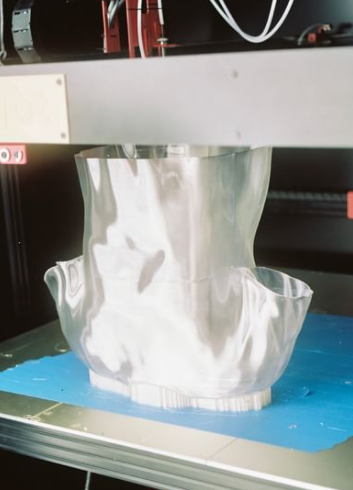

Her collaboration with JWA therefore takes different forms from the set to the actual clothing. The most obvious relationship seems to be in the sculptural leather dresses that opened the show in bubbly champagne, soft pink and deep red. Paradoxically, their shape presents the fluidity of a light fabric enliven by the wind and movement of the body, but traps this fleeting moment in a rigid heavy material that does not move with the body on which it is cast. “The flick of a dress, frozen in time” according to the show notes. Beyond the material, the reference to life and the mundane put the pumpkins and dresses in conversation. The whole show seems to be a reflection around fluidity and the relationship between the fabric and the body, in turn being the sculpting and the sculpted. In a reflective dynamic, the fashion sculpts the body and the body sculpts the fashion.

The second silhouette is a car-dress offering another opportunity to ponder on the movement associated with clothing. The Italian futurists are famous for their obsession with the premises of machine-engineered movement, and the way to capture the relationship between the stillness of the canvas and the movement it represents. For Anderson, “Eye can feel texture in a big bang that starts from the beginning of mankind and jumps to the industrial revolution.” The third silhouette seems to be gaining in fluidity as only the top is cast in a transparent plastic 3-D sculpture giving the body more visibility, literally and figuratively.

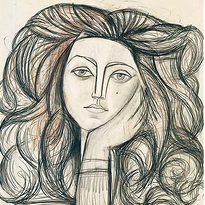

Moving away from hard leather and plastic, dresses and tops are then cast in felt and oversized bombers become the main attraction, allowing for greater comfort and movement of the body and by such moving away from the sculptural definition (used here as noun and attribute) of hard clothing. Then, dresses are at the intersection of fluidity and stillness with a chest cast in the shape of lips and silky lengths before featuring sculpted balloons as brassieres, or all over the body, playing with fitted and oversized, alternatingly revealing and hiding the body. Body shapes are printed on the fabric, or manifested by their absence, like for the shoes in the mesh dresses. This obsession with the body is a clear reference to Salvador Dali (of which the muted palette aligns with those of the show, the overall neutral hues allowed for a better focus on the shapes and fabrics used) and even Elsa Schiaparelli, the first ambassador of surrealist fashion.

Accessories are also replete with art historical references, from the furred shoes akin to Meret Oppenheim’s tea set, or featuring glass balloons, or looking like present wrapping bows or seatbelts, while clutches look like actual sculptures, fur-lined and shell-like shaped (and even a bracelet designed by of the Loewe Craft Prize winner, Genta Ishizuka). As the show progresses, the clothes seem to be gaining in fluidity and practicality as the fabrics get softer and the fits less tailored, the final looks being probably the most practical of the whole show, if practicality was ever a goal. According to the show notes, “Touch is stimulated: leather, felt, latex, tweed, knit, 3D printed fiber, silk, resin. Movement is caught, objects are trapped.” and our minds are expanded.

Interestingly, the Surrealist movement that emerged after the First World War (as we seem to get into the Third one), aimed at moving away from the rationalism that they thought led Europe to rip itself apart. They aimed at offering an alternative reality, “an absolute reality, a surreality,” in the words of poet and critic André Breton, author of “The Surrealist Manifesto” published in 1924. Surreality which is obviously driving JWA’s creativity. His fascination with the strange, odd, almost cringe asks what seems to now be an eternal question of whether or not fashion needs to be obsessed with the beautiful, or what beautiful even means. Like art, fashion does not have to be seductive to express a message. With this collection, Anderson expands the vocabulary of fashion and offers a broader range of meaning to luxury fashion, beyond what meets the eye only…

Leave a comment