Comme des Garçons is probably among the most original high fashion brands, founded by the Japanese Rei Kawakubo in 1969, it plays on the notions of gender, high and low, and established standards of beauty. Her work broke industry norms with items that were, and still are not necessarily flattering, subverting body shapes and classical fashion. If there is a commercial appeal to her heart-filled line of ready-to-wear, her brand identity has been built on serving the underground, avant-garde communities.

She came to light globally with her debut show in Paris in 1981, and claimed she wanted to start from scratch, wishing to look at clothes without the weight of history. The main argument made by Kawakubo relates to the shape of the items that, in Western clothing are least, are expected to match and enhance the natural shape of the body. Her dresses are shapeless, fully black at her debut.

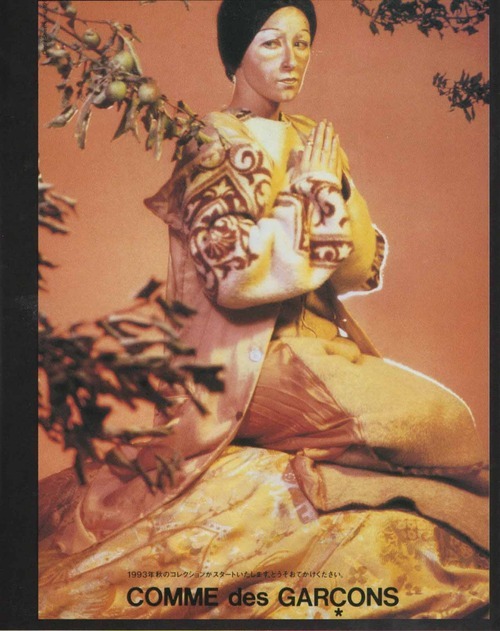

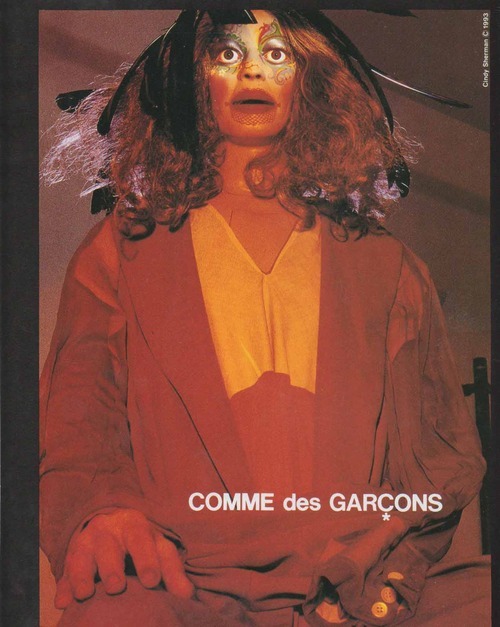

Her collaboration with Cindy Sherman for the 1994 campaign of Comme des Garçons, therefore almost feels natural when looking at the career of the artist. Indeed, Cindy Sherman is an American photographer famous for her raw and direct representations of society. She rose to fame with her “Untitled Film Stills” in the 1970s, a series of black and white pictures of herself referencing typical women roles in performance media.

Both are women who made it in a men’s world and earned outstanding recognition for their work challenging societal norms, within the fashion industry and the art industry. Sherman had already participated in some fashion collaborations before, as her Untitled series had established her ability to use mass-media references to criticize her contemporary consumerist society. This materialized in works with media like Vogue and Harper’s Bazaar.

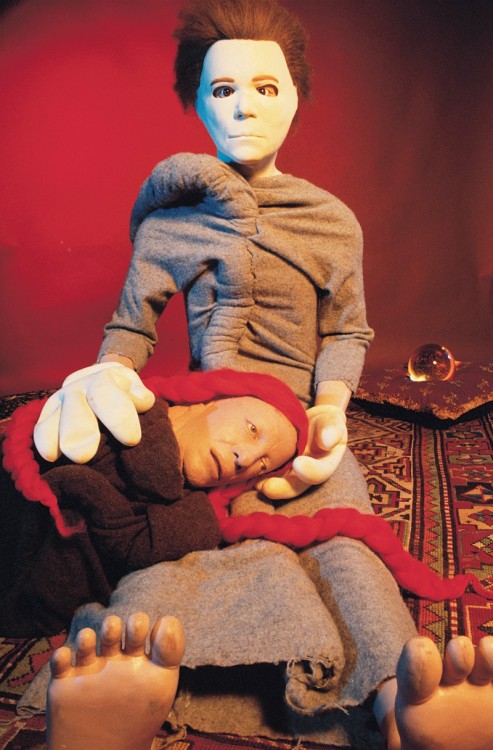

The 1994 campaign, reflecting the Comme des Garçons aura, was not the classical glossy polished fashion campaign that were (and still are) flooding fashion magazines. Cindy Sherman’s dark interpretation of fashion advertising went against the grain and uncovered the story-telling power of fashion, beyond the party-infused, tight luxury values traditionally attributed to the industry. Art has always been political, and fashion can also be a powerful tool to make a political point. Therefore, collaborations with artists feed the credibility of the brand to make such a point, while giving the artist a chance to reach a wider audience. This often implies, especially in recent years, performing more commercial pieces.

Yet, nothing seems commercially oriented in this campaign which is closer to an engaged art piece than a money-making campaign. The pictures are anything but appealing, the mannequins are ridiculed and distorted to an uncanny degree, while the clothes are not the focus of the campaign made to advertise them. The mannequins have running make-up, disheveled hair, or scary masks akin to a horror movie while the bruises recall the sexual violence addressed by Sherman in the 1992 “Sex Pictures” series. Even in a picture more traditionally aesthetically pleasing, like Untitled (#296) featuring the artist herself parred in luscious white feathers, looking at a mirror ball, the clothes are not the subject of the shoot, although they clearly represent the signature style of Comme des Garçons.

Clothes, as much as photography, are a means of communication. In “The Fashion System”, philosopher Roland Barthes dives into the semantics and the communication power of fashion and fashion photography in particular, enabling viewers to project themselves into the idea of what they want to reflect to society through clothes. This powerful mechanism is marketed and commercialized by fashion magazines, which are here challenged by Sherman. In the same fashion, Comme des Garçons offers a subversive medium of expression to its wearers, by questioning the message that they want to convey with their clothes. By going against the glossy and corseted representation that fashion magazines and traditional brands present as the ultimate end, Comme des Garçons questions the conventions of self-representation and self–identification.

According to Jessica Glasscock, “If Sherman’s take on Kawakubo’s designs is difficult to discuss as fashion photography, that difficulty is mirrored in the fashion press’s attempts to come to terms with Comme des Garçons clothes.” They destabilize the beauty and communication standards but also, ultimately, the way of doing business in the fashion industry, as well as what the audience might be responsive to and spend their money on. Similarly, Sherman is non conventional as her work criticizes consumerism and capitalism, as well as commercial appropriation. This campaign, therefore, by critically looking at its subject, reinforces and legitimates the ties between art and fashion, beyond the mere consumption aspect that currently dominates the field.

Leave a comment