On the (self-)invisibilization of women in creative spheres.

Going into 2022, it is safe to say that feminism – and questions related to gender – have permeated every aspect of our societies, or at least, awareness of inequalities have. In many industries and crafts, women have been overlooked and fashion is no exception. Truth is, in an industry where women are the main target (not to say the product), it can be counterintuitive to see men making the bulk of the decisions, even today, from top executives to established designers. Acne Studios deciding to work with the Hilma af Klint foundation in 2014 therefore speaks both to what the brand stands for and, is an opportunity to look at engaged art and fashion collaborations, beyond design.

Fashion creation and artistic creation are two different spheres, but in the past century, they have both faced increased commercialization. Art is being increasingly commodified, and fashion has been institutionalized as a status symbol regulated by large fashion corporations and their Maisons. This goes hand in hand with increased globalization and a larger, more connected audience, directly impacting these businesses top lines, and therefore, the stakes. De facto, in many ways, the structural forces at play in the art world and within the fashion industry are representative of the wider social realities.

In the case of women artists, the scholarly article “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?” by Linda Nochlin, sheds light on how and why women have been excluded from the craft for centuries and have been invisibilized by cultural tastemakers, that is, men. Because fashion as an industry only emerged during the 19th and 20th century, it is harder to claim women had no visibility for the centuries in question. In fact, artisans were not given the same credit as designers are nowadays. Quite interestingly, for centuries too, artists were not recognized as such and the character of the artist as a gifted genius only appeared during the Renaissance period. Yet, it is safe to say that the establishment of fashion as a business did not include women as decision makers, most of the time for the simple reason that they were not in charge of financial decisions. Of course, in both cases, there have been some notable exceptions, and this trend has been slowing during the twentieth century.

In fact, it is interesting to look at the structural interplays applicable to both women artists and fashion designers. In her article, Linda Nochlin underlines that women did not have the same opportunities to become an artist because they were not supposed to get educated. And when they started to gain access to the classroom, the classical education involved classes such as nude drawing to which they were not allowed to take part. What is more, women were supposed to stay at home to take care of the household and had less free time to dedicate to their craft.

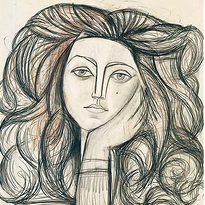

What is more, painting or sculpture requires tools, a studio or the ability to travel, that made the craft more complicated than picking a pen and writing. There have been some notable exceptions, like Artemisia Gentileschi or Rosa Bonheur, but a dive into their social origin reveals their ties to the art world, making it easier for them to challenge the status quo. And even then, they were never considered as men’s equal. Well into the 20th century, the deep belief that women’s art was below men’s art permeated the artworld. Lee Krasner, known for most of her life as Mrs Pollock, was told by Hans Hoffman, “This is so good you wouldn’t know it was done by a woman.” in 1936.

While the scheme is slightly different for fashion, it is also rigged with inequalities. If the first designer to rise to international fame was Rose Bertin, Marie-Antoinette’s dressmaker, the designer considered to have invented the modern luxury industry, that is, a fashion house powered by a designer and financed by a businessman, was Charles Frederick Worth. Men had always dictated what was appropriate for women to wear, permeating social norms and policing women’s bodies in corsets and heavy fabrics, but with Worth, it was institutionalized. Up to today, women are under-represented at top fashion houses decision-making tables.

Looking only at creative direction, there has not been any women designer at Louis Vuitton, Maria Grazia Chiuri is the first woman designer at Dior, Karl Lagarfeld was the creative director of Chanel longer than Coco Chanel even was. According to Luxe Digital, out of the 10 most popular luxury fashion brands, 4 have women at their artistic helm. Yet, Muccia Prada shares it with Raf Simons, Donatella Versace took on after her brother’s death, and Virginie Viard was named after Karl Lagarfeld’s sudden death.

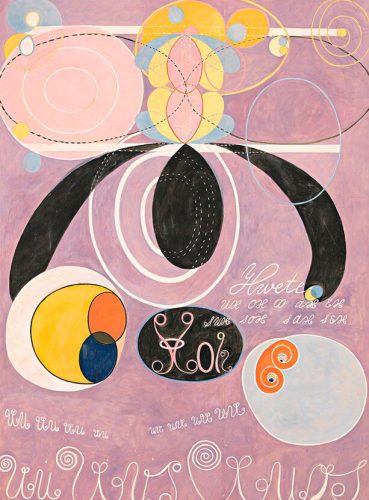

The example of Hilma af Klint is striking in many aspects. Her work remained secret for more than 20 years after her death as she dubbed it too avant-garde for her contemporary audience, therefore choosing herself not to be seen as opposed to her male counterparts. What is certain is that she was acutely aware of the social realities of the time and place she lived in. Only recently rediscovered in 1986, mounting evidence suggests that she was at the forefront of abstraction at the beginning of the 20th century. She started exploring abstraction around 1906, years before artists like Vassily Kandinsky, Kazimir Malevitch or Piet Mondrian. Deeply inspired by spiritualism and theosophy, her work forms a complex ecosystem where paintings are part of a larger purpose. Acne Studios deciding to dedicate a capsule collection to her work is therefore a welcomed opportunity for visibility for a woman artist that has remained utterly unknown for the bulk of the past century.

Interestingly though, the Acne Studios collection features genderless clothing, presented as a menswear collection, made of sweaters and shirts. If the brand has always been known for creating that type of genderless fashion, it is interesting to note the totality of the engagement taken with this collection. Acne Studios is breaking the gender boundaries from creative direction to creative features (af Klint’s work) to target audience, which was still quite original back in 2014.

The message sent is that not only our society is ready to receive af Klint’s work, but it is also ready to give its due space within our cultural canons. Clearly, boundaries are not what they used to be within the creative sphere at large, but much remains to be done on the gender fronts. This is true not only for women but also for underrepresented trans-gender groups, at every step of the creative, distribution, and communication process.

Leave a comment