When dance meets luxury fashion

Gabrielle Chanel was known for her relationships with the important cultural figures of her time, especially artists across disciplines such as dance, painting and literature. When she was a young seamstress, she already had great admiration for legendary dancers such as Caryathis and Isadora Duncan. If they certainly had an impact on her fashion, she never brought art to the runway in an overt fashion like some of her contemporaries would do, nor did she revendicated art as being an inspiration.

Yet, she considered dance as the utmost expression of the freedom of the body, a key motivation of Chanel’s work as she is still famous for liberating women’s bodies. After centuries of women being painfully tied into tight corsets and covered in elaborately draped fabric, Chanel chose to reveal the body’s natural outline in comfortable pieces. It was as revolutionary as Cubism… Her collaboration to the realization of the famous Le Train Bleu ballet with the Ballets Russes dance company in 1924 therefore comes as no surprise.

Even before working with her close friend Serge Diaghilev on the costumes of his company’s newest ballet performed at the theatre des Champs Elysees, she funded the realization of Le Sacre du Printemps, still the most famous ballet of the above mentioned avant-garde movement. Le Train Bleu, subject of the ballet in question, was a famous train linking Calais, North of France, to the Cote d’Azur, and was favored by the elites of the 1920s, among which Chanel herself. It consisted of 10 exclusively first-class sleeping cars that were decked out in a midnight blue velvet upholstery with mahogany trim, and one upscale dining car that served five-course meals. The exterior was painted “a shimmering dark blue with gold accents,” according to Stegall, earning it its name: Le Train Bleu.

It was representative of quintessential luxury, and the ballet treated the subject both as a celebration of fashion and a satire of superficiality. As Diaghilev indicated in a playful program note, ”The first point about ‘Le Train Bleu’ is that there is no blue train in it. This being the age of speed, it already has reached its destination and disembarked its passengers.” The spectator discovers the dancers at the seaside where two couples flirt and fight among a herd of gigolos and flappers. The ballet is full of references to the craziness of the 1920’s, from sunbathing and snapshots to movies and maillots.

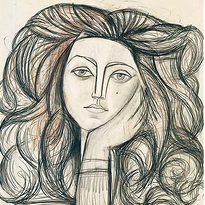

In the South of France, these elites would be lounging, dressed in Chanel as represented by Picasso himself (in his first Bathers work, a theme that he would decline profusely in the following decades). Picasso also participated in the making of the ballet, designing the stage curtains while the libretto was produced by Jean Cocteau, the score by Darius Milhaud, the sets by Henry Laurens, and the choreography by Bronislava Nijinska, reuniting the artistic leaders of the time and creating an interesting inception of the subjects by themselves.

The Ballets Russes was as famous for its highly original sets and costumes as for its music and choreography. Incidentally, the success of the initial representation testifies of the status of the company at the time, as a journalist complained, ”It is as difficult to get a seat for ‘The Blue Train’ as it is to get a seat for the thing itself during the height of the Riviera rush.” Yet, the dance company stopped performing it after the departure of the main dancer Anton Dolin in 1925, well before the actual decline of Le Train Bleu along the rise of air travel.

Chanel was the first Maison de Couture to make costumes for ballets. Interestingly, Karl Lagarfeld also contributed to the dance and fashion tradition at Chanel by creating the costumes for two ballets by the German choreographer Uwe Scholtz in 1986 and 1987. In 2009, he created the outfit for dancer Elena Glurdjidze for the Swan Lake Ballet at the English National Ballet in London and the costumes for the dancers of the Brahms-Schönberg Quartet at the Paris Opera with the dance director Benjamin Millepied.

These numerous collaborations contributed to adding an artistic layer to the fashion designs, yet focusing on the practical aspect more than other fashion brands collaborating on artistic endeavors. Cut and fit are essential elements within the luxury industry, but they are even more critical for a practice where movement is the main attraction. These collaborations inscribe Chanel’s craftsmanship cultural relevance and expands the reach of the Maison beyond simple fashion, giving status to an already admired brand and contributing to the aura and patrimony of the Maison.

On the other hand, dance companies get visibility and the insurance of being dressed by the best craftsmen of their time. This dependence, just starting to be explored when Chanel worked with the Ballets Russes, is applicable to future intertwining of fashion and other artistic disciplines and explain why they have not ceased to gain in popularity and efficiency since then. If it was certainly a collaboration between people who admired each other’s work and was participating in the cultural avant-garde of the time, it has nowadays become a well-rounded marketing and commercial performance that is mainly run to boost sales. All year round. Could anyone have predicted this phenomenon at the time of Chanel? Probably not.

Leave a comment